[Submitted to the inaugural Horne Prize, 2016 – presented by The Saturday Paper]

He answers the door in shorts, a t-shirt with the face of Che Guevara emblazoned across it. It’s an unseasonably warm autumn day, and so his feet are bare. In place of his famous Stetson is a red baseball cap.

Ian ‘Molly’ Meldrum, short and slightly hunched and yet instantly recognisable despite his seventy-three years, stares quizzically at me as he leans against the partially open door, a small dog running about behind him barking, high-pitched. The door is set into a tall, yellow concrete wall on a quiet street in an inner-city Melbourne suburb. On either side of the wall’s doorway, on the outside for all to see, are stencilled metre-high replicas of the logos for both the St. Kilda football team and the Melbourne Storm, outfits Meldrum has a long history supporting.

He doesn’t say anything, so I introduce myself, remind him we spoke on the phone yesterday, and that we’re meeting for a chat – I’m interviewing the iconic Australian music industry personality for a book I’m writing on the history of the Australian rock press, which this year celebrates fifty years since its inception. It all started, essentially, via the pop paper Go-Set, for which Meldrum was a long-running contributor prior to his days as host of the popular Countdown television program.

He nods his head in recognition – ‘Yep’ – and invites me inside, into the small front garden to the doorway of the house itself, a double-wide terrace in which he’s lived for years. I ask him if I should remove my boots, he shrugs, so I kick them off and walk into the house, the sunshine receding behind us as we make our way down a dark hallway, dodging the accumulated belongings of a lifetime spent in the music industry, into the lounge-room.

It’s lighter down this end of the house. The room opens up through glass doors onto a bricked terrace with a small swimming pool to the side, a mirror ball suspended over the still, blue water, a giant sarcophagus head mounted on the high wall at the end. Meldrum has an affinity with Egypt and its culture, he’s been there countless times and so there are Egyptian themed artefacts littered all about the place, they meld into the framework of a house which is more museum than dwelling; Pharaoh heads and sphinxes affixed to walls alongside signed photos of John Lennon and Yoko Ono, gold records and pictures of Meldrum with the likes of Elton John and Paul McCartney.

He tells me to take a seat on the couch.

As he sits down the other end, picking up a milky bowl of cereal from the coffee table, which he resumes eating, I launch into my book spiel, tell him what it is, exactly, I’m doing, and what I’d like from him. He nods intermittently, keeps eating his cereal. On the table in front of us, among the detritus – books, unopened mail, CDs, ashtrays and the like – I place my Dictaphone, and open my notebook which I balance on my knee. I ask him my first question, looking over at him as I finish, waiting for his reply.

It doesn’t come.

Meldrum looks at the floor in front of him, spoons another mouthful of cereal, keeps looking down. I wait, nervous now. His mobile rings, and he places the bowl on the coffee table and answers it. It’s a journalist from the Herald Sun, I can hear her voice clearly, she’s asking him for a comment on something to do with naming Melbourne laneways after famous musicians. He listens, answers in one or two words, listens again, then tells her he’s in an interview and can she call back.

He hangs up, puts his mobile down, picks up the bowl and takes another mouthful, resumes looking at the floor. Tentatively, wondering if he’ll speak to me at all, I ask him my initial question again. This time, to my relief, he looks up and seems to think. He starts talking.

***

My father couldn’t stand him. I was never sure why at the time, I was probably only about eight or nine. Every time we all sat down to watch Hey, Hey It’s Saturday though, and Molly Meldrum’s segment came on, Dad would furrow his brow and grumble, get up to make himself a cup of tea.

“What an eedjit,” he’d say to no one in particular as he walked into the kitchen.

A few years later, no longer watching Channel 9’s long-running variety show but coming across Meldrum more and more as I began to ingest popular culture prior to the year I was born, I thought that maybe Dad didn’t like him because of the homosexual thing. As it turned out though, my sister is gay, and Dad went on loving her without missing a beat.

In hindsight, now I’m older again, I think it was Meldrum’s manner that so infuriated Dad. Coupled with the music he was talking about (with which Dad would surely have had no connection), the be-hatted commentator’s trademark almost stream-of-consciousness style of talking, his hair-brained way of getting his point across, would have been anathema for my old man; Dad, before he died late last year, was very straight-to-the-point, which is something Ian ‘Molly’ Meldrum has never been accused of being.

“Molly churned out his… stream of consciousness, drowning in a sea of ellipsis, as I described it for years,” laughs Phillip Frazer, who along with Tony Shauble, founded Go-Set in 1966. I’d spoken to Frazer at length almost nine months prior to meeting Molly, and he’d given insight into the man himself. Indeed, just reading Meldrum’s columns which began to appear in the long-defunct paper not long after its inception, you can see where his jump-around style of communicating originated, in print before it ever graced Australian airwaves.

I get a taste of this as our chat builds momentum – I’ll ask about the entertainment sections of the major newspapers of the time and within seconds, we’re talking about Meldrum being a surfer down in Lorne; I ask him about the first issue of Go-Set, if he remembers seeing it, and before I know it we’re talking about Ronnie Burns, with whom Meldrum lived for years.

And yet it all makes sense. When I transcribe the interview a day or so later and read through it afterwards, there’s nothing Meldrum says that isn’t interesting or a part of the story, at least in some regard – his style is just to talk as it comes, which it eventually all does. What’s amazing is his recall; after half a century in an industry well known for its excesses, his memory of it all is remarkably clear.

That half century began in mid-1966. “I came in and there’s a guy sweeping the floor,” Frazer had told me. In those early months, Go-Set was produced out of a house in Malvern, a comfortable suburb in Melbourne’s east. Meldrum had turned up looking for some sort of work and Shauble had pointed him towards the broom. Frazer lobbed in, and there he was.

“He knew more, because he was a groupie, a band follower… he knew more about the local scene than anybody I’d met at that point,” Frazer remembers, and it was because of this knowledge that Meldrum became, soon afterwards, an integral part of this fledgling publication.

“Everything,” Meldrum says immediately when I ask what he got from writing for Go-Set. “It gave me a purpose you know?” It certainly gave him a beginning.

***

I would have sat down with Meldrum months earlier if I’d been able. I tried a number of times before it finally happened, a litany of missed opportunities and close calls that resulted in the situation just never coming to be. My contact was journalist Jeff Jenkins, who co-wrote Meldrum’s biography, The Never, Um, Ever Ending Story, which was published in late 2014. Jenkins tried his best to facilitate a meet, and his efforts eventually paid off, at least for me. He emailed me Meldrum’s number in March this year, and told me he was expecting my call.

I was nervous. A couple of other journalists had told me that he was hard to interview, that his attention span was limited and that he was likely to evade questions, instead just talking about whatever he felt like. He’d suffered a couple of well publicised accidents – a serious fall from a ladder in 2011, and an accident in Thailand only a couple of months before we met – and so he was reportedly not as ‘with it’ as he used to be.

Standing in a friend’s Coburg backyard though, I made the call, emboldened by numerous cups of instant coffee, and while he didn’t come across as overly enthusiastic about my talking to him, he offered his home as a venue for our chat, and we were finally good to go.

***

We talk, on the record, for around an hour. After the initial false start, Meldrum warms to the subject, one which is obviously close to his heart. He talks of bands and artists like Johnny O’Keefe, Olivia Newton John, The Twilights, Marcia Hines; he talks of The Beatles’ fabled 1964 Australian tour and how it then impacted upon the fledgling Australian music scene; he tells tales of going out all night and sleeping in his car before being woken by production assistants and then going on air on Kommotion, the television show he was involved with for a while at the same time he wrote for Go-Set, a show which has been credited with being an influence on Countdown.

He laughs as he calls his good friends Michael Gudinski and Michael Browning, who started Daily Planet, a short-lived rival to Go-Set, “hippies and radicals”. He smiles and laughs as he remembers things, things that happened when Australian music was young and growing and anything was possible. Things that happened when the Australian rock press was young and growing and anything was possible.

We finish up the interview, talking about The Beatles. “I love John, I loved both of them (Yoko), and Paul has always remained a good friend, and George was a friend,” Meldrum says, pointing to a couple of framed pictures hanging on the lounge room wall. Meldrum was the journalist who, in the pages of Go-Set, broke the news that the band was breaking up, after interviewing Lennon back in 1969.

I ask if he still keeps in touch with any of the remaining members. “Yeah, Paul all the time,” he smiles. “And Yoko as well.”

I turn off the Dictaphone, close my notebook, put it on the table. Meldrum asks if I want a cup of coffee – ‘Sure, if you’re having one’ – he gets up and walks slowly to the kitchen where he puts the kettle on. I sit and look around, pat the dog which is sitting on my foot, look out over the small courtyard where the sun is reflecting off the pool mirror ball throwing shards of dancing light all about the place.

He comes back with a full cup, he walks slowly these days, carefully puts it down on the coffee table in front of me, sits back on the couch and picks up a packet of cigarettes. He asks if I mind, which I don’t, I pull out tobacco and roll up, he passes me a lighter and we sit in his lounge room and smoke. He’d said on the phone, the previous day, that he was busy and we’d only have an hour, but he seems quite content to continue talking, even though the formal part of the interview is over.

He tells me how, only a week or so prior, he’d had a party at his place for his Melbourne Storm mates, “Around 160 people in here,” he says with a laugh, waving his arm about the house which while reasonably roomy, would struggle to fit a heaving mass of humanity within its walls, even a small one, given the amount of paraphernalia leaning and piling and squatting in almost every available inch.

He tells me about his Storm mates, and how he’s friends with Queensland league legends Jonathan Thurston and Greg Inglis – I grew up in central Queensland, weaned on a steady diet of rugby league from an early age, and so I hang on his every word. I’m a Brisbane Broncos supporter, so we swap footy stories for a while. He asks about Phillip Frazer. We talk about Byron Bay. He slowly ashes his cigarette into one of the ashtrays littering the table top.

“Molly is a staggeringly principled person,” Frazer had told me. I can believe it. He sits on the front edge of the couch, his hands together between his knees, gnarled fingers playing with the large rings which adorn same, slowly scuffing his bare feet on the rug. Even engaged, he keeps his head bowed for the most part; he comes across as honest, humble, principled indeed. Most of all, he comes across as passionate, even after all these years; as passionate now as he would have been when, as a youngster, he began his journey, writing for Go-Set, back when it began for everyone.

The Australian music press was the medium which brought Australian music culture to international attention, and launched the careers of not just countless musicians, but writers, editors, publishers and photographers, simultaneously providing a voice for an entire cultural movement. Meldrum was there for the beginning, and as such, became a crucial part of the Australian music press, and as a result, of Australian culture.

I finish my coffee, butt out my third or fourth smoke. I tell him I need to be off, I’ve another interview somewhere else in Melbourne this afternoon. He doesn’t get up, but offers his hand and smiles as we shake, tells me I know more about “bloody Go-Set” than he does.

I leave him sitting on his couch in his cluttered lounge room, the sun still dancing off the mirror ball outside, surrounded by a life in music. I make my way down the dark hallway, out the front door where I put my boots back on. I walk out the front gate and close it behind me. I make my way through the quiet streets to the tram stop back into the city. I leave an Australian icon behind me.

Samuel J. Fell

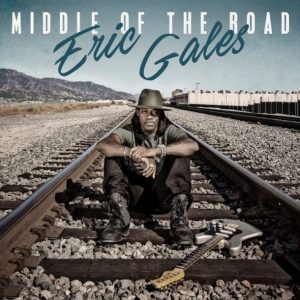

Hailed early on as a child prodigy on the guitar, Gales released his first album as a teenager, a heady melding of a range of rootsy designs with a strong rock presence, a fusion as he says. And this has been his signature ever since – based in the blues yes, the blues will always be number one to Gales, but he fosters a want to explore the myriad possibilities thrown up via hybrids of multiple styles.

Hailed early on as a child prodigy on the guitar, Gales released his first album as a teenager, a heady melding of a range of rootsy designs with a strong rock presence, a fusion as he says. And this has been his signature ever since – based in the blues yes, the blues will always be number one to Gales, but he fosters a want to explore the myriad possibilities thrown up via hybrids of multiple styles. Middle Of The Road stands as a sort of reinvention for this modern bluesman too, inspired by all he’s gone through thus far (ailed H“Just life man, surviving,” he laughs, explaining the inspiration in a nutshell). As he says in the record’s accompanying press material, “It’s about being fully focused and centered in the middle of the road. If you’re on the wrong side and in the gravel you’re not too good, and if you’re on the median strip that’s not too good either, so being in the middle of the road is the best place to be.”

Middle Of The Road stands as a sort of reinvention for this modern bluesman too, inspired by all he’s gone through thus far (ailed H“Just life man, surviving,” he laughs, explaining the inspiration in a nutshell). As he says in the record’s accompanying press material, “It’s about being fully focused and centered in the middle of the road. If you’re on the wrong side and in the gravel you’re not too good, and if you’re on the median strip that’s not too good either, so being in the middle of the road is the best place to be.”

There’s another part to it however, that “I don’t really talk about,” she confesses – this part goes deeper. “The band’s always been a democratic process as to what’s recorded, what goes onto albums, how [the albums are] recorded, basically it’s sort of fight for your song a little bit, get out-voted.”

There’s another part to it however, that “I don’t really talk about,” she confesses – this part goes deeper. “The band’s always been a democratic process as to what’s recorded, what goes onto albums, how [the albums are] recorded, basically it’s sort of fight for your song a little bit, get out-voted.” “So we made the plan to meet up in Josh’s unfinished house, and that was the extent of it,” she explains. At that point, other than wanting to make an album to thank their fans, they had little idea of what they wanted to come out with. There’d been no pre-production, no back-and-forth, just a germ of an idea that was to make a record.

“So we made the plan to meet up in Josh’s unfinished house, and that was the extent of it,” she explains. At that point, other than wanting to make an album to thank their fans, they had little idea of what they wanted to come out with. There’d been no pre-production, no back-and-forth, just a germ of an idea that was to make a record.

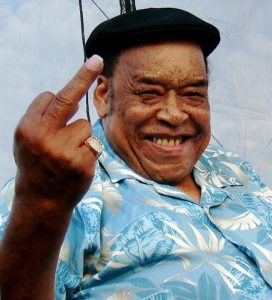

James Henry Cotton died on Thursday March 16, in Austin, Texas. He was 81, and while perhaps unknown to people not familiar with the blues, the man was a behemoth – a working musician by the time he was nine, he cut his teeth under Sonny Boy Williamson II, before branching out and recording with the great Howlin’ Wolf for Sun Records. Then, as a 20-year-old, he joined Muddy Waters’ band, where he stayed for a decade or so, before moving out solo – a legend of blues harmonica, Cotton recorded a slew of albums under his own name over the years, and was still touring three years ago when he made his first trip to Australia.

James Henry Cotton died on Thursday March 16, in Austin, Texas. He was 81, and while perhaps unknown to people not familiar with the blues, the man was a behemoth – a working musician by the time he was nine, he cut his teeth under Sonny Boy Williamson II, before branching out and recording with the great Howlin’ Wolf for Sun Records. Then, as a 20-year-old, he joined Muddy Waters’ band, where he stayed for a decade or so, before moving out solo – a legend of blues harmonica, Cotton recorded a slew of albums under his own name over the years, and was still touring three years ago when he made his first trip to Australia. Opposite me sit Hat Fitz and Cara Robinson. They have breakfast on the table in front of them, half empty green smoothie looking things, and as you’d expect, they’re exactly the same offstage as they are on it. Hat leans back, ubiquitous work shirt and stubbies, thongs, an old cap atop his head, long beard framing his face. Cara is dressed nice, stylish, glasses and hair just so. They seem, at a glance, an odd couple, but they’re a perfect couple. One listen to their music and you know that for a fact.

Opposite me sit Hat Fitz and Cara Robinson. They have breakfast on the table in front of them, half empty green smoothie looking things, and as you’d expect, they’re exactly the same offstage as they are on it. Hat leans back, ubiquitous work shirt and stubbies, thongs, an old cap atop his head, long beard framing his face. Cara is dressed nice, stylish, glasses and hair just so. They seem, at a glance, an odd couple, but they’re a perfect couple. One listen to their music and you know that for a fact. It’s very powerful, even more so given there are only two of them, and it’s a fine pointer as to what the rest of After The Rain holds.

It’s very powerful, even more so given there are only two of them, and it’s a fine pointer as to what the rest of After The Rain holds.

It’s an industrial scene, towering iron sheds arching over concrete throughways and rusty bollards, the incongruous and ramshackle Pirates Tavern across the lot from the Outdoor Stage where All Out Exes Live In Texas harmonise over a bed of accordion-led merriment, guitar and mandolin and ukulele skipping carefree alongside. This quartet has come a long way in a short time and the overtly sweet nature of their music, at times in the past too syrupy sweet, has a harder edge to it today, their sound a little tougher, although this makes it no less beguiling. It seems at odds with its physical surrounds, and yet draws it all together in a way which makes sense. People tap booted feet on old and cracked concrete. It does all make sense.

It’s an industrial scene, towering iron sheds arching over concrete throughways and rusty bollards, the incongruous and ramshackle Pirates Tavern across the lot from the Outdoor Stage where All Out Exes Live In Texas harmonise over a bed of accordion-led merriment, guitar and mandolin and ukulele skipping carefree alongside. This quartet has come a long way in a short time and the overtly sweet nature of their music, at times in the past too syrupy sweet, has a harder edge to it today, their sound a little tougher, although this makes it no less beguiling. It seems at odds with its physical surrounds, and yet draws it all together in a way which makes sense. People tap booted feet on old and cracked concrete. It does all make sense.