[Published in Rolling Stone (Aust.), April 2017]

Bluesfest 2017 – A Celebration Of Eclecticism, by Samuel J. Fell

Tyagarah Tea Tree Farm, Byron Bay – April 13-17

(for all pics by Carl Neuman, head to the Rolling Stone website here for slideshow…)

While the others get their bags from the back of the truck, pull on boots and check pockets, I lean against the bullbar and roll a cigarette. There’s no breeze to speak of and so the smoke drifts straight upward into the clear evening air. It’s warm enough for shirtsleeves, but cool enough for jeans, boots, the rains of the past month, the tail-end of the destructive Cyclone Debbie, all but gone, nothing here to remind of the devastation, the damage, the life-changing consequences of which are still evident elsewhere, but not here.

The carpark was under water a week and a half ago but today, this evening, it’s dry and lush grass, no mud, cars parked in orderly rows, stretching off as far as you can see. The sun is setting and the sound of a frantic kick drum thuds across the vast spaces, people flocking towards it, walking past us, around us, heading towards the North Gate and entry into the Byron Bay Bluesfest, this year gearing up for its 28th go ‘round.

We stroll in the same direction, and as we mix with the throng, I’m already looking for The Face. As Hunter S. Thompson tried to do in his iconic Kentucky Derby piece from 1970, I’m looking for The Face which best epitomises this gargantuan festival, that truly represents all that this happening is about. In truth, I’m not so much looking for The Face, as I am The Person – the person, their dress, their demeanour, their very being, that sums up how this all plays out. For the past 28 years, as this festival has grown into the multi-faceted event it is today, so to have its followers and so I’m looking for the one which best brings it all together, which tells the tale as it should be told.

I discreetly gauge people from the corner of my eye as we pass them, looking them up and down, trying to ascertain if they’re the one I’m searching for or not.

A grizzly old fucker, glimpsed mid-laugh, gaping mouth with only a handful of teeth (fair bet some bloody-knuckled lout in some sweat and smoke-stained barroom somewhere, has the other handful), a grotesque image that seems to freeze as it happens, and it sticks in my mind for hours afterwards.

Once inside, I meander up to the Media tent and am offered an interview with Rhiannon Giddens, which I take and am escorted into the artist area, where I sit with Giddens and guitarist/producer Dirk Powell for twenty minutes, talking about her latest cut, Freedom Highway, and her impression on a festival she’s appearing at this year for the second time.

“There are a couple of different criteria, for an artist,” Giddens says, on how she rates Bluesfest. “First of all, there’s vibe of the festival, and there’s the nuts and bolts, how they take care of you as an artist. And this one hits all of it… they help us set up the sideshows, and they take care of us from day one. I’ve always said, you feed a musician good, they’ll follow you around forever, you know what I mean?”

She and Powell both laugh. We finish up and I head back out, down the long road between the Mojo and Crossroads stages and out into the festival itself, hungry for music having spoken to Giddens, lured by the bright lights of food and clothing stalls, the flashing strobes on stages, navigating the sparsely populated site with ease (Thursday is unofficially referred to as Locals Thursday, the big crowds not in attendance until Friday, room to move and stretch, see bands in a more intimate setting, a good soft warm-up for the days to come).

I see Snarky Puppy who lay down steaming swathes of dissonant prog, a thundering set that thrashes about seemingly at random but which then comes back to where it should, continuing on without missing a beat. It’s not an easy listen, but essentially follows the rules and so after one is used to it, it’s easy to tap your feet to, to at least guess where they’re going next.

Which can’t really be said for the Miles Electric Band, who follow up on the Crossroads Stage. Not that they’re not exemplary musicians (a good portion of the band appeared on Miles Davis’ seminal Bitches Brew, and his nephew is behind the kit), but this is jazz, real jazz, Davis Jazz – it bucks and humps, ducks and weaves about, this is truly dissonant. It pulses with a real power though, because you know, through the squeaks and squawks, the thunder and the pitter patter that this is what it’s supposed to be. Players go off on instrumental solos from which there seems no return; there are rhythmic sojourns and horn-laden freak-outs – the crowd is small but they dig it, and the set is good and strong, something different, something you feel is real, long after it all mysteriously winds up.

An old woman, surely closing in on 90, sitting on an upturned milk crate at the back of the Delta stage, draped in rainbow cassock with sandals on her feet, her long and stringy grey hair down to the small of her arched back. She’s delicately eating some sort of frozen ice-block, a dangerous purple colour, careful not to let it melt on her hand as she taps her feet to the roadie sound-checking the bass drum up on stage, a seeming world away from where she’s sat.

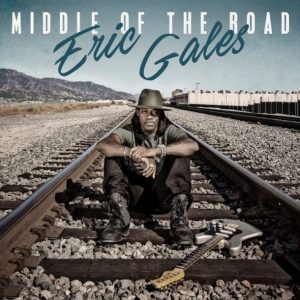

Glimpses: Mavis Staples (The Queen) plays out with soulful aplomb once more on the Jambalaya Stage; Nikki Hill and band (what a band), shred the Delta Stage into millions of tiny pieces; Jeff Lang, with Greg Sheehan on percussion, creates small tempests that gust hard before slowing tenderly and then upping again, one of the most inventive players on the planet; Eric Gales, who festival director Peter Noble calls “the best guitarist in the world”, wields his instrument like a weapon, bass and drums behind him, backing vocals, they breathe new life into the electric blues; Booker T. Jones leading the STAX Revue, a critical time in musical history brought to life, somewhat, in Byron Bay, a little flat but very hard to deny the strength of the music itself; Mud Morganfield, son of Muddy Waters, a crack backing band who specialise in steaming Chicago blues – Morganfield has a strong voice (luckily, otherwise this’d just be a wan tribute act), and he takes control and this is good, solid, robust and muscular blues.

I walk up to the Mojo Stage late on the Thursday night to see Patti Smith and band perform her seminal 1975 release, Horses. It’s a visceral set, a lithe and lanky thing which confuses then consumes and keeps consuming, Smith’s band consummate in the background, Smith out the front a Beacon as she begins to build and build the set, brick by brick, line by line, as she starts to find within herself the rhythm which the rest of the hour or so then forms.

“THIS FUCKING CORRUPT WORLD,” she almost vomits this line, her face creased with disgust and it’s a line which sticks hard in my head and I’m not even sure what it’s in reference to, so lost am I in the cadence of her voice, the rhythm with which she’s railing, her voice and the bile and passion rising and falling to the rhythm of her own making, her band, her tight band, almost superfluous by this point – she spits fire and venom, she’s lost no heat with the passing of time, with the onset of age, her long braided grey hair whips her face, her long and pointed aquiline nose juts from her face like a single, defiant mountain, pointing wherever she projects her piercing eyes… this isn’t so much music as it is poetry and brimstone and disgust and hate and power and passion. So much passion. There are tears in the audience. There’s a heat, a tingling around the heart like everyone, to a man, has been stirred and wants, nay needs, to do something.

It’s a set which has, according to Noble, been a good few years in the making, but it’s worth the wait and there’s little one can do afterwards but head home to the comfort of bourbon and beer chasers, kicking off boots and settling into bed and quiet.

A young girl, maybe 20, sitting cross-legged on the grass in the sun behind the Crossroads Stage, immaculately dressed, carefully and fastidiously applying thick, red lipstick to narrow pale lips, oblivious to the myriad people stepping around her, gazing into her small mirror painting deep red with an almost translucent, careful hand.

Friday through Sunday bring full houses, not so much a crowd as a crush, a roaring, seething, shouting mass of skin and bone, sweaty muscle in multi-coloured muslin and floppy hats, bumping from one stage to the next, the bars and food queues, ATM lines and clumps of people grouped on the grass, tripping over deck chairs in the dark, strollers lit with fairy lights, small children on shoulders with pink ear-muffs and mouthfuls of organic donut.

Courtney Barnett is great on Thursday, grinding melodic grunge, a true urban poet telling takes most ordinary, so ordinary they’re relatable to all and this is what makes it work. Nas, with the brassy N’Awlins Soul Rebels backing, searingly combines these two musical forms and it kicks, it’s thundering second-line hip hop, the horns feeding the beat, Nas himself feeding back off it all, rap on brass, the sousaphone providing the bass.

An old bloke, the epitome of the acid-washed-out generation, adorned in glitter shirt and pink sunglasses, rainbow sombrero atop his balding pate, strung with wreathes of yellow rubber duckies – a photographer spies him and asks him to pose, which he does, but with shirt open revealing a spilling, white, slightly speckled gut, it queers an already dubious deal.

By comparison, another ‘90s hip hop superstar, Mary J. Blige, is comparatively beige. Blige is an exemplary performer, her band are tight, but as I noted at the time in my daily Rolling Stone wrap-up, her rather slow R&B seems dated, she herself a little less energetic. Perhaps the power and passion exhibited by Nas, the previous night, paints Blige’s set in a paler light, the latter just not able to come out of that tall shadow. Blige is good, but this one doesn’t kick.

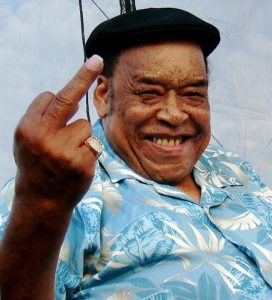

For mine, the same could be said (and it pains me to say this about one of my favourite acts on the planet) for Buddy Guy’s set, at least his Sunday run. The last of the old school bluesmen, Guy is finally showing his age, he’s a little slower and seems a little more scattered than on previous visits, his usual flowing medleys stop-starting, Guy adding commentary before playing the next snippet, killing any sense of momentum. That said, when Guy sets his fingers right, he still wails with the best, in fact he is one of the best, still firing. Perhaps the last time we’ll see him in Australia though.

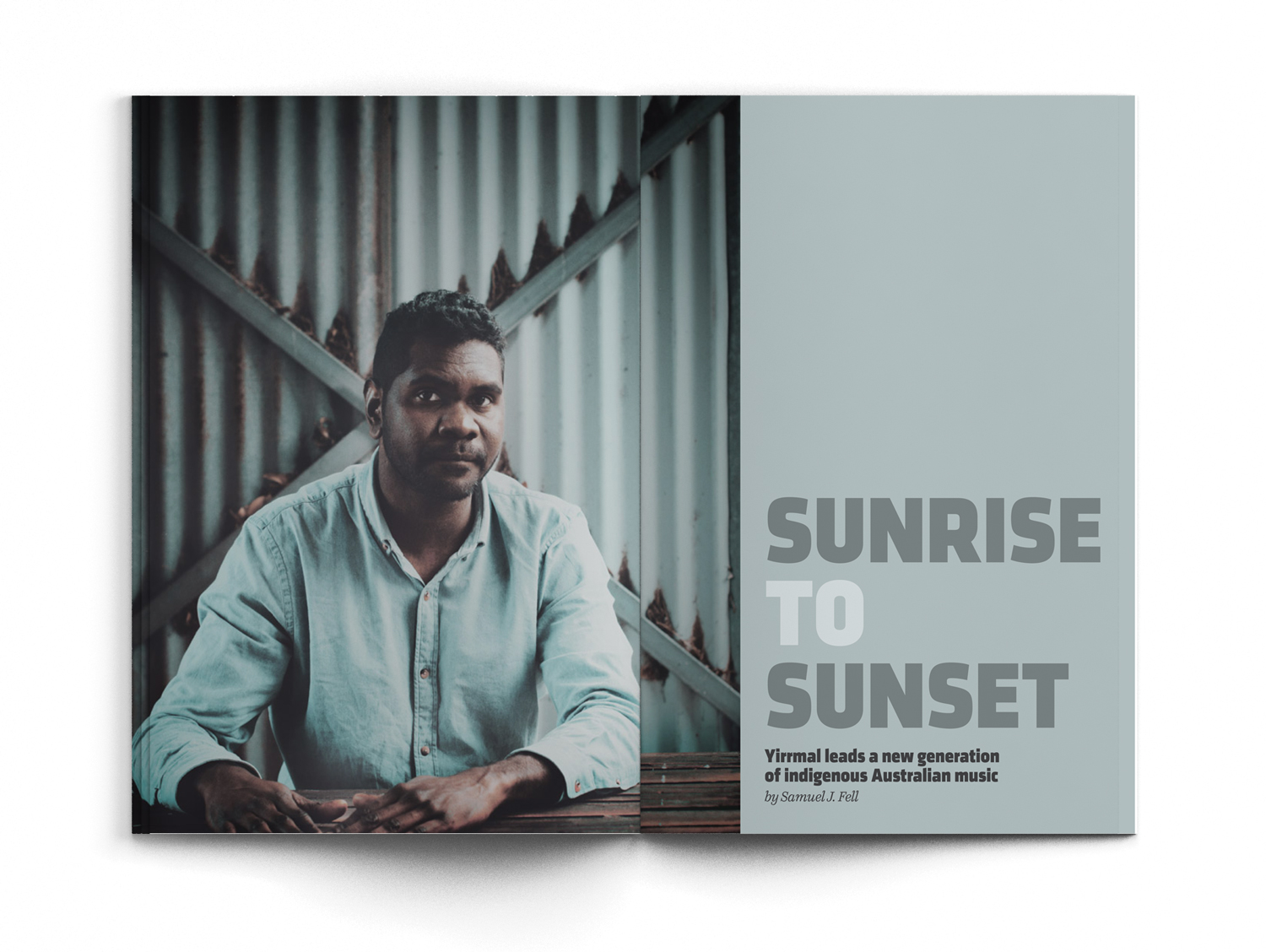

I wander down to the Juke Joint stage in the early Friday afternoon heat to see up-and-comer Yirrmal perform as part of the Boomerang Festival but a lineup change sees party-starters OKA in his place, so I catch a bit of them and while they’re solid, I find the beat a bit too heavy for this time of day, and so head off lamenting not being able to hear Yirrmal’s voice in the live setting, where word is it truly shines. No matter, for there’s no doubt he’ll be back here again, on the main bill – and while we’re on this, I look forward to the day Boomerang attracts enough investors to launch properly on its own as a champion of indigenous music and culture, but kudos to Noble and Bluesfest for continuing to support it in the meantime, even if all the acts involved would fit just fine in Bluesfest proper.

And while we’re on ‘festivals within festivals’, Carlos Santana and band create their own unique event on the Sunday night, a rhythmic juggernaut from which there seems little respite, not that anyone wants any – this booms and throbs, Santana’s guitar instantly recognisable, particularly via Abraxas mainstays Black Magic Woman and Oye Coma Va, classic tracks set against a starry sky that are truly beautiful to behold. The crowd heaves and it’s a street party in tent but it bursts at the seams and overflows into the rest of the festival and people dance regardless of age, gender, face, inhibition.

A young kid, maybe ten years old, marching with committed resolve towards the South Gate from the hot and listless carparks, lagging behind his parents clutching two cucumbers, one half eaten, clutching them like someone will take them away, intent on eating both flavourless vegetables before someone tells him he can’t bring them inside and he’s left with nothing.

Bonnie Raitt stuns on Friday night, her band in tow, a true leading lady of the roots music world; Jimmy Buffett confuses, veering from country (which is deep and solid) to calypso, which is light-hearted and, to my mind, lacks substance, but the Parrotheads (his diehard, and slightly loony, followers) disagree and in their purple shirts, parrot hats and coloured beads and what not, they cheer and dance and revel in what this most odd and famous of men is laying down, he dances on stage and looks like a red-cheeked gnome, playing guitars and generally being happy, which one gets the impression, is his main state of being. They do a calypso, steel drum-led version of Crowded House’s Weather With You, which as you would imagine, garners much love, dozens of parrots nodding in unison, which is indeed, an odd sight, and one to behold for sure.

“We wanted to reclaim a language, it’s not a dead language,” says Joe Henry, referencing the railroad-inspired folk songs he and Billy Bragg followed, researched, lived in making their recent record, Shine A Light. They play them together on the Jambalaya stage on Monday afternoon, their voices rising as one, two acoustic guitars, Americana and blues and folk slipping off the stage wrapping up all in attendance, the belief this pair have in the music the true power behind it – a festival highlight.

At the same time, across the way, Australian blues and roots icon Lloyd Spiegel, in his first Bluesfest appearance, holds his own full house in the palm of his hand, just him and his trusty Cole Clark, a full swag of songs, a full tote of stories told with humour and aplomb, the man able to make his guitar do anything at all as he tells tales both tall and true, his own superbly written material marrying with blues standards in a way few others are able to manage. The man is a mountain, and he’ll surely be back.

Glimpses: Melody Angel is possessed of a rare power, her voice an anvil from which are forged songs of immense strength, Chicago blues and rock ‘n’ roll, she graces stages all weekend and slays it every time; the Zac Brown Band, big American slick country, full ensemble, all of whom are experts on their chosen instruments – I don’t like their records, but live they’re another deal altogether and it’s hard not to get drawn into their world, whether quiet and reflective or raunchy and country, it’s all full force music shined to a Nashville sheen, their version of Charlie Daniels’ Devil Went Down To Georgia a highlight, thanks in large part to the fiddle playing of Jimmy de Martini.

Spell Design-clad blondes with reflective Ray Bans and floppy felt hats; older, well-heeled couples in button-down shirts and crisp shorts, camping chairs slung over shoulders with water bottles and sensible hats; bearded blokes with Jack Daniels t-shirts and leather Harley Davidson vests; beer-brand singleted bros, stumbling about in packs, three cans apiece, six sheets to the wind; faux hippies and harpies, mods and rockers, clean and feral, stoned and clear.

I don’t find The Face. And no, as it is in Thompson’s story, the face isn’t mine, as cracked, chipped and vaguely distorted as the old mirror into which I gaze come Tuesday morning. For there really is no one face that, truthfully, defines what this festival is all about. Whether your aim is to spend five days sitting on the same stool in the VIP bar, talking with whoever comes near, or whether it’s to find yourself as much music as you possibly can, tripping through the throngs as you traverse the festival site again and again, there is no one face.

As, with the festival, there is no one sound, style, genre or artist. Bluesfest, despite its name, is an eclectic beast, one which strives to find and showcase the best in roots music, and this is a wide umbrella – as such, it heaves and thrashes, a multi-limbed beast, eclectic, one that doesn’t just tick a single box, but dozens. The people who patronise it are the same, all different, all odd and strange in their own way, and this all combines to make the Byron Bay Bluesfest what it’s become over the years. And this is a good thing to be sure.

As we wander out the South Gate, late on the Monday night, having traversed the grassy site dozens of times, having gulped at the sonic stew with countless others, bumped and been bumped, laughed and pointed, eyed off, sucked down, imbibed and over-eaten, it’s with a stinging sense of completion, not a sense of wanting, and despite the fact I didn’t find The Face, I found the sound, the sounds, from all around, and so there’s little to do but retire home to the comfort of bourbon and beer chasers, kicking off boots and settling into bed and quiet and beginning to count down, once again, the days until next year.

Samuel J. Fell

In the old town, Jaffa and its ancient port, lights are lit and music tumbles from old, arched doorways despite the time of day and we sit on the top deck and drink Israeli beer after we’ve put her to bed and we catch up, smoking in the still air, wafting upward. The new city burns bright in the middle distance, white light, while below us basks in yellow, the flickering painting the cobbled streets in ever-changing layers of light and shade. Stray cats prowl and the purple bougainvillea spews over an old grey wall like spent beer from a bottle left in the freezer overnight.

In the old town, Jaffa and its ancient port, lights are lit and music tumbles from old, arched doorways despite the time of day and we sit on the top deck and drink Israeli beer after we’ve put her to bed and we catch up, smoking in the still air, wafting upward. The new city burns bright in the middle distance, white light, while below us basks in yellow, the flickering painting the cobbled streets in ever-changing layers of light and shade. Stray cats prowl and the purple bougainvillea spews over an old grey wall like spent beer from a bottle left in the freezer overnight. et should I come across somewhere to drink coffee while we’re out but I never do, nothing is open this early. We have the old streets to ourselves and we make for the water, along the foreshore, into the maze of the port and upward, upward, steps and slopes, warn smooth from centuries of feet, so many feet, up to the crown of the hill overlooking it all and down the other side. Across the wishing bridge. Past the church facing west. Into the shade and bustle of Yefet and into the market where nothing is open and we’re hidden from the sun under shade of narrow paths and old, faded sun-shades stretched across alleys entwined with electrical wires and ornate strands of fairy lights and wreaths of coloured cloth.

et should I come across somewhere to drink coffee while we’re out but I never do, nothing is open this early. We have the old streets to ourselves and we make for the water, along the foreshore, into the maze of the port and upward, upward, steps and slopes, warn smooth from centuries of feet, so many feet, up to the crown of the hill overlooking it all and down the other side. Across the wishing bridge. Past the church facing west. Into the shade and bustle of Yefet and into the market where nothing is open and we’re hidden from the sun under shade of narrow paths and old, faded sun-shades stretched across alleys entwined with electrical wires and ornate strands of fairy lights and wreaths of coloured cloth.

Hailed early on as a child prodigy on the guitar, Gales released his first album as a teenager, a heady melding of a range of rootsy designs with a strong rock presence, a fusion as he says. And this has been his signature ever since – based in the blues yes, the blues will always be number one to Gales, but he fosters a want to explore the myriad possibilities thrown up via hybrids of multiple styles.

Hailed early on as a child prodigy on the guitar, Gales released his first album as a teenager, a heady melding of a range of rootsy designs with a strong rock presence, a fusion as he says. And this has been his signature ever since – based in the blues yes, the blues will always be number one to Gales, but he fosters a want to explore the myriad possibilities thrown up via hybrids of multiple styles. Middle Of The Road stands as a sort of reinvention for this modern bluesman too, inspired by all he’s gone through thus far (ailed H“Just life man, surviving,” he laughs, explaining the inspiration in a nutshell). As he says in the record’s accompanying press material, “It’s about being fully focused and centered in the middle of the road. If you’re on the wrong side and in the gravel you’re not too good, and if you’re on the median strip that’s not too good either, so being in the middle of the road is the best place to be.”

Middle Of The Road stands as a sort of reinvention for this modern bluesman too, inspired by all he’s gone through thus far (ailed H“Just life man, surviving,” he laughs, explaining the inspiration in a nutshell). As he says in the record’s accompanying press material, “It’s about being fully focused and centered in the middle of the road. If you’re on the wrong side and in the gravel you’re not too good, and if you’re on the median strip that’s not too good either, so being in the middle of the road is the best place to be.” There’s another part to it however, that “I don’t really talk about,” she confesses – this part goes deeper. “The band’s always been a democratic process as to what’s recorded, what goes onto albums, how [the albums are] recorded, basically it’s sort of fight for your song a little bit, get out-voted.”

There’s another part to it however, that “I don’t really talk about,” she confesses – this part goes deeper. “The band’s always been a democratic process as to what’s recorded, what goes onto albums, how [the albums are] recorded, basically it’s sort of fight for your song a little bit, get out-voted.” “So we made the plan to meet up in Josh’s unfinished house, and that was the extent of it,” she explains. At that point, other than wanting to make an album to thank their fans, they had little idea of what they wanted to come out with. There’d been no pre-production, no back-and-forth, just a germ of an idea that was to make a record.

“So we made the plan to meet up in Josh’s unfinished house, and that was the extent of it,” she explains. At that point, other than wanting to make an album to thank their fans, they had little idea of what they wanted to come out with. There’d been no pre-production, no back-and-forth, just a germ of an idea that was to make a record.

James Henry Cotton died on Thursday March 16, in Austin, Texas. He was 81, and while perhaps unknown to people not familiar with the blues, the man was a behemoth – a working musician by the time he was nine, he cut his teeth under Sonny Boy Williamson II, before branching out and recording with the great Howlin’ Wolf for Sun Records. Then, as a 20-year-old, he joined Muddy Waters’ band, where he stayed for a decade or so, before moving out solo – a legend of blues harmonica, Cotton recorded a slew of albums under his own name over the years, and was still touring three years ago when he made his first trip to Australia.

James Henry Cotton died on Thursday March 16, in Austin, Texas. He was 81, and while perhaps unknown to people not familiar with the blues, the man was a behemoth – a working musician by the time he was nine, he cut his teeth under Sonny Boy Williamson II, before branching out and recording with the great Howlin’ Wolf for Sun Records. Then, as a 20-year-old, he joined Muddy Waters’ band, where he stayed for a decade or so, before moving out solo – a legend of blues harmonica, Cotton recorded a slew of albums under his own name over the years, and was still touring three years ago when he made his first trip to Australia. Opposite me sit Hat Fitz and Cara Robinson. They have breakfast on the table in front of them, half empty green smoothie looking things, and as you’d expect, they’re exactly the same offstage as they are on it. Hat leans back, ubiquitous work shirt and stubbies, thongs, an old cap atop his head, long beard framing his face. Cara is dressed nice, stylish, glasses and hair just so. They seem, at a glance, an odd couple, but they’re a perfect couple. One listen to their music and you know that for a fact.

Opposite me sit Hat Fitz and Cara Robinson. They have breakfast on the table in front of them, half empty green smoothie looking things, and as you’d expect, they’re exactly the same offstage as they are on it. Hat leans back, ubiquitous work shirt and stubbies, thongs, an old cap atop his head, long beard framing his face. Cara is dressed nice, stylish, glasses and hair just so. They seem, at a glance, an odd couple, but they’re a perfect couple. One listen to their music and you know that for a fact. It’s very powerful, even more so given there are only two of them, and it’s a fine pointer as to what the rest of After The Rain holds.

It’s very powerful, even more so given there are only two of them, and it’s a fine pointer as to what the rest of After The Rain holds.