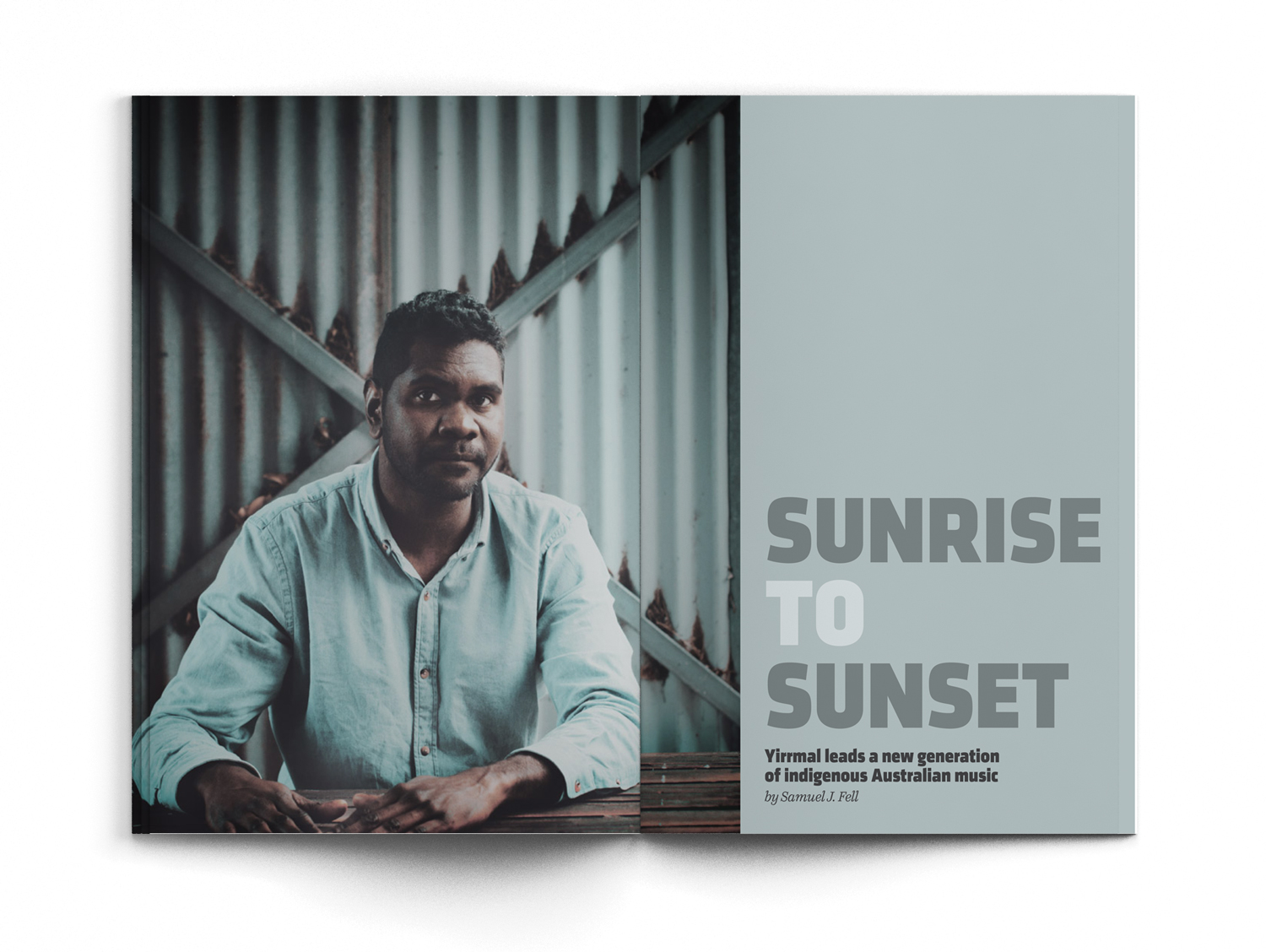

[Published in Rolling Stone, April 2011, COVER FEATURE]

The Deep Part

Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu might be one of Australia’s most enigmatic figures, but his second album, Rrakala, is all about showing the rest of the world how he lives.

By Samuel J. Fell

Silence. Complete and utter silence. Not for long, maybe only ten seconds or so, but a silence that threatens to consume the four of us sitting in the control room at Byron Bay’s Studio 301, if not for what came before it. Music as primal and raw and gritty as can be, yet as sweet and ethereal as sunshine after a storm, streaks of sound wrought from the heavens themselves, translated by a man as unassuming as it’s possible to be. Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu, nodding his head slowly as what he’s just played becomes memory, his hands finally, after seven and a half minutes, resting in his lap.

Michael Hohnen, Gurrumul’s accompanist, producer and long-time friend, is smiling. Sound engineer, Anthony Ruotolo and his assistant are smiling as well, and I’m struck dumb, sitting at the back of the room, notepad abandoned on the table in front me, wondering to myself where the music I’ve just heard could possibly have come from, and how I’ll possibly be able to describe it. The song, played on an out of tune piano – due to the heat in the studio, Gurrumul needing it to be as close to the tropical humidity of Darwin as possible – was a rough version of ‘Ulminda’ which will eventually appear on Rrakala, what will become Gurrumul’s much anticipated second solo record. He’d finally wandered in, sat down, and just played this song, virtuosic, his voice on a plain nigh on improbable, its purity astounding.

“I remember the moment,” muses Hohnen a few days later, sitting on the grass outside the studio during our first of many interviews for this story. “It’s very exciting working with him when he goes into that mode of ‘Nothing else matters and I’m focusing just on the moment and this musical situation’.

“And that is music in its most pure form, I think, when you experience what you and I did that afternoon. In some ways it’s kind of why you live or why you are a musician, to go through those sorts of moments…and there was so much energy around what he did as well which was really special. It was almost like he pushed his chest out at the end of it, he knew it was really special.”

“It really is all about the performance,” adds Ruotolo a few months later from New York where he’s based. “Our job as engineers is to capture as accurately as possible those critical nuances of that performance. When Gurrumul is in his zone, it’s something very special.”

As far as Gurrumul himself is concerned, it’s a lot more simple. “It’s about the head, you know, it’s the deep part,” he says through Hohnen, tapping his head gently a few times, just a couple of inches above his forehead, giving that look as if it is very serious. “’Ulminda’ means the deep part.”

Earlier that first day, I’d sat with Hohnen and we’d listened through the entire album as it stood thus far; 12 un-mastered, unmixed tracks, the bare bones that would eventually come together to make up Rrakala. Gurrumul himself wasn’t present at that point, preferring instead the solitude of their apartment, not in the mood to enter the studio, content to lie on his bed listening to music. I wondered if I’d get the chance to see him in action, but didn’t press, and after a few hours of listening and talking, I got in the car to drive back to Brunswick Heads, 15 minutes up the highway, and before I left I asked Hohnen to let me know if Gurrumul decided to come into the studio.

It was bright outside, more so because of the gloom I’d been sitting in for the best part of the morning, and I squinted all the way home, pulling in, parking, walking up to the house, putting on the kettle with the intention of sitting down to go through my notes, and then my phone buzzed, a text message from Hohnen. “If you want to turn around,” it says, “he’s about to do piano.” I jumped back into the car.

***

The fact Gurrumul will only come into the studio when he feels like it, interests me somewhat. As both Hohnen and Ruotolo have pointed out, when he’s on, he’s really on, but as Ruotolo then says, “I think it is a very delicate place, where he draws his inspiration from, and on the days that he may feel like maybe he isn’t there emotionally, he leaves it alone.” Hohnen and Skinnyfish Music co-owner, Mark Grose, have learnt to roll with these situations, it’s part of working with an artist like Gurrumul.

The flip-side however, is worth the wait. “Yeah, when he’s on, he’s totally on,” reiterates Hohnen. “The night before [you were there], he didn’t want to go to bed. The others were exhausted, but he was going, ‘Maybe you and I can do something’, so he just wanted to keep going. So when he’s in that mode, he’s really focused. And he’s so connected to back home, he’s always on the phone back home, it’s almost like he’s there more than here a lot of the time. But when he walks through that door and the phone’s not on, he knows that, essentially, this is his voice for the next few years, he knows that this is representing him, so he’s really conscious about that.”

***

In 2008, Gurrumul released, through Skinnyfish Music, his eponymous solo debut, a record which took the planet by storm, shaking its very foundation. It wasn’t the first time he’d been exposed to the world – Gurrumul has a songwriting credit and an ARIA for ‘Treaty’ (amongst other songs), performed by Yothu Yindi with whom he played for many years (guitar, keys and vocal), and is a part of the Saltwater Band – but it was the first time he’d been laid bare on his own. His rise, which is well documented, was swift, and as such there’s a lot of anticipation as to whether this new record will match the first.

“He’d never say this, but I would think he would hope, or probably expect, it to be popular, because it’s really strong,” says Hohnen. “He’s put some very strong songs forward. One of the songs, ‘Baru’, is about the crocodile, it’s all about him, and I think he would expect people would like it, because it’s like him singing totally about himself and his identity. But if I ask him if he thinks this record will go well, he’ll ask me that back, it’s one of the questions he won’t answer.”

Indeed, when asked, Gurrumul merely says, “Just doing more songs. Like the first album but different. With piano. I just like these songs too. Maybe people will like it.”

***

The base difference between Gurrumul and Rrakala, is that Gurrumul plays drums and piano in addition to the guitar on this record. “Gurrumul is a multi-instrumentalist,” Ruotolo tells me. “I spent a few days with him where he wasn’t near a piano, then all of a sudden he sits down and it sounded like he had been playing every day, perfect fluid playing. I watched him lay down a drum groove at Avatar in NYC (where the bulk of Rrakala was recorded, early last year) in, like, one or two takes! And it was solid! That’s what struck me most about him, his ability to pick up an instrument and go.”

Then there are the subtle differences, the ones that are set to elevate this record, guiding Gurrumul’s star even higher. Watching him in the studio, it’s his confidence which strikes me, his ability to really push what he’s doing now, like he’s no longer afraid of anything, although again, according to Gurrumul it’s not like that.

“Michael and I knew people liked the first CD,” he says. “This is a bit the same for this one. People like it, you know. I want something that people like.” Hohnen expands. “He and I are sort of reaching into that well of his, which is so deep and the only way he wants to really expose that well, is through his music. There’s a lot of stuff in there, in his head, that never comes out, from the light stuff you’ve seen, the banter, the humour, but also all the cultural stuff. And this is his balance he’s found between the deeper cultural sides of himself.

“We’ve been trying to work out how we’d actually present the second album, and I think presenting it as him and his identity is probably the strongest way we can do it.” It’s a way which has seen Gurrumul rise to the occasion, and as such, the music itself benefits – Rrakala booms with confidence, it radiates power and at its core is Gurrumul himself, still the same as he was when portrayed on Gurrumul, but bigger and stronger.

***

“When I watch him sing, it’s not like watching an opera singer,” Hohnen says of Gurrumul a few months after the time spent in 301. “With an opera singer, you can almost see what they’re doing, it’s this learned process…that’s the first thing I think about when I compare him singing, how you’ve seen watching him up close; they’re doing something that’s learned and formalised and I find it’s almost less inspiring…they’re still acting, most singers are acting.”

“So when you’re confronted like you were up close with Gurrumul, it’s like you’re presented with something that is not following the path of all those other people,” he adds, searching for the right words. “I’m sure there are singers out there who are actually not acting that much, like some of the punk singers, you know? Some of them are acting, but some of them are just singing so much about what they believe in, and that’s what he’s doing; he’s singing totally, totally what he believes in, he’s not trying to be someone else, he hasn’t watched anyone else, so he doesn’t have to look a certain way, he’s just going, ‘I’ve listened to the great singers all my life, and the great traditional singers all my life, and I need to project like that to get recognised’, I think that’s how he works. I think that’s why it’s so refreshing.”

As I leave the studio on one of the three days and nights I spend there, I say goodnight to Gurrumul, accidentally mispronouncing his name – more of a ‘Garrumul’ instead of ‘Goorrumul’ – which Hohnen later tells me Gurrumul found very funny. He still finds it funny, three months after the fact. During those sessions too, he laughed a lot and made jokes with Hohnen, interspersing takes with yips and howls, then he’d turn around and play an amazing piece of music. Of all the musicians I’ve interviewed, at all stages and ages and levels of popularity, not one of them has been as humble and naïve and truly free of hang-ups as Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu. This is a man with his feet firmly on the ground, purely because he knows of no other way.

“That’s right,” agrees Hohnen. “He’s just being himself because that’s all he can be.”

***

During the writing of this piece, Gurrumul and Hohnen fly down to Sydney to do the accompanying photo shoot. I speak to Hohnen the night before and he’s excited because Gurrumul is “excited about the photo shoot”, the reason being he actually understands the gravity of appearing on the cover of a magazine such as this one. “For years I have had to put up with Gurrumul’s taste in music being different from mine,” Hohnen then wrote to me via email whilst the pair of them waited in the airline lounge in Darwin on their way to Sydney the next day.

“Sure we both like lots of the same music too, but Dr. Hook is never a band I bought CDs of…years ago I remember he says, “Michael, you like this one?” and plays me a scratched CD he is carrying around. It is the Dr. Hook song ‘Jungle To The Zoo’. Gurrumul loves it, and I do too. I never remember hearing it back in the ‘70s.

“So we go to the airline club and have some lunch waiting for the plane. I get out my phone and play a YouTube link to him. He starts laughing from the first few bars of the music – the funny and clever and entertaining Dr. Hook song, ‘The Cover Of The Rolling Stone’ comes blaring out of my phone, in the no-phone area of our lounge and a man looks over sternly at me. I don’t stop it because the pleasure of the moment is too great. Gurrumul, who ironically will never see it, is totally excited to be getting what one of his favourite bands sang about. It’s a great clip on YouTube too. It’s a Powerpoint presentation of lots of jpegs of famous Rolling Stone covers and I flick between watching it and Gurrumul’s grin, whilst he listens to the familiar recording, rocking, funking and clunking away.”

***

I ask Gurrumul who he writes these songs for. “It’s just a meaning, that song, it is just about that part of the mind,” he says, meaning ‘Ulminda’. I ask about songs in general. “Some for family, or other Yolngu (the collective noun for all north east Arnhem people who speak this language). Some for my father or uncle. Or kids to hear in the future. They’re stories, like everyone writes songs.”

I ask where these songs come from, how much he draws on his cultural past, his cultural identity (the saltwater crocodile), his people. “This one is what we know, Yolngu, what we know about how we know things,” he tells, still referencing the ‘Ulminda’ song, before expanding. “From our stories, and our life. Then I change them into songs. Like Balanda (white people) do too, you know? We have a lot of knowledge, so when me or other family write things, it is just describing things that happen…it comes from spirit. I am just singing from spirit.”

I then ask about Gurrumul’s family and how they impact upon his music, how it’s relevant to them, despite the fact it’s been thrust into the western spotlight. “They are everything. All family,” he says. “I sing some song they write too. Like ‘Bayini’ on this new album, and a funeral song and another one by my brother Johnno Yunupingu, and another song by Saltwater lead singer Manuel (Dhurrkay).”

“My family encourage me,” he goes on. “They want this to be happening. They want people to know about Yolngu. Family and people just say this is what they want, to show what we know to the rest of the world. To educate people about our world and our lives, and how we think and live. It’s different. It’s different.

“My family is everywhere.”

***

I’d asked Hohnen at some point how it made him feel to watch Gurrumul really nail something. When he came in to play ‘Ulminda’ in particular – here he was, making the most of an imperfect situation, what with the piano being out of tune. Hohnen talked about Gurrumul’s strength, and it occurred to me that that performance was true of Gurrumul’s whole life. Here is a man in an imperfect situation, being blind from birth, making the most of it, and then some, which is something Hohnen attributes to all indigenous people. “Yeah, that’s part of their survival technique in a way,” he explains.

“But I see that everyday,” he goes on regarding Gurrumul’s strength as a person, as a musician and artist. “When there’s something he doesn’t want to do, there’s nothing that will change him. But when there’s something he does want to do, he really makes it happen. And that’s probably what’s happened more with this second record, there was no hesitation about anything to do with it; the New York trip, the Byron trip, the photo shoot…it’s just part of what happens.”

What has happened here, what I witnessed and what I’ve been told is almost mythical. Watching him play in the studio, smoking a cigarette with him outside, having him remember who I was and what I was doing, being able to communicate with him, albeit through Hohnen for the most part, this is all a surreal experience because of how he is. Gurrumul isn’t a ‘normal’ musician, and this has little to do with the fact he’s blind. Yes, his blindness does colour how he acts and portrays himself, because he can’t emulate other people, other performers.

But it’s all so real. And from that, comes this music. Rrakala. In an industry sense, an incredibly anticipated release, but in a musical sense, to Gurrumul, a collection of songs that tell a story and serve no other purpose than to educate and enlighten and to be enjoyed. As Hohnen mentioned more than a few times, it’s refreshing, Gurrumul himself is refreshing. In the ten seconds of silence that followed his off-the-cuff performance of ‘Ulminda’ when I first saw him in the studio, it’s like I’m transported into Gurrumul’s head where nothing else matters, everything is free and it’s all about that one, single moment. And yes, that is refreshing.

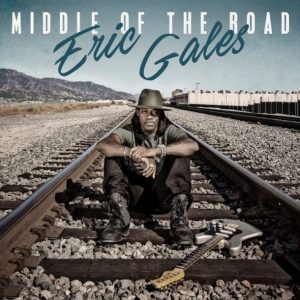

Hailed early on as a child prodigy on the guitar, Gales released his first album as a teenager, a heady melding of a range of rootsy designs with a strong rock presence, a fusion as he says. And this has been his signature ever since – based in the blues yes, the blues will always be number one to Gales, but he fosters a want to explore the myriad possibilities thrown up via hybrids of multiple styles.

Hailed early on as a child prodigy on the guitar, Gales released his first album as a teenager, a heady melding of a range of rootsy designs with a strong rock presence, a fusion as he says. And this has been his signature ever since – based in the blues yes, the blues will always be number one to Gales, but he fosters a want to explore the myriad possibilities thrown up via hybrids of multiple styles. Middle Of The Road stands as a sort of reinvention for this modern bluesman too, inspired by all he’s gone through thus far (ailed H“Just life man, surviving,” he laughs, explaining the inspiration in a nutshell). As he says in the record’s accompanying press material, “It’s about being fully focused and centered in the middle of the road. If you’re on the wrong side and in the gravel you’re not too good, and if you’re on the median strip that’s not too good either, so being in the middle of the road is the best place to be.”

Middle Of The Road stands as a sort of reinvention for this modern bluesman too, inspired by all he’s gone through thus far (ailed H“Just life man, surviving,” he laughs, explaining the inspiration in a nutshell). As he says in the record’s accompanying press material, “It’s about being fully focused and centered in the middle of the road. If you’re on the wrong side and in the gravel you’re not too good, and if you’re on the median strip that’s not too good either, so being in the middle of the road is the best place to be.” There’s another part to it however, that “I don’t really talk about,” she confesses – this part goes deeper. “The band’s always been a democratic process as to what’s recorded, what goes onto albums, how [the albums are] recorded, basically it’s sort of fight for your song a little bit, get out-voted.”

There’s another part to it however, that “I don’t really talk about,” she confesses – this part goes deeper. “The band’s always been a democratic process as to what’s recorded, what goes onto albums, how [the albums are] recorded, basically it’s sort of fight for your song a little bit, get out-voted.” “So we made the plan to meet up in Josh’s unfinished house, and that was the extent of it,” she explains. At that point, other than wanting to make an album to thank their fans, they had little idea of what they wanted to come out with. There’d been no pre-production, no back-and-forth, just a germ of an idea that was to make a record.

“So we made the plan to meet up in Josh’s unfinished house, and that was the extent of it,” she explains. At that point, other than wanting to make an album to thank their fans, they had little idea of what they wanted to come out with. There’d been no pre-production, no back-and-forth, just a germ of an idea that was to make a record.