It used to run the Melbourne lines.

Dark laps of the underground City Loop before exploding – rattling like crooked death on twin steel pins – into the faded southern light and heading east to Lilydale, north to Upfield and Craigieburn, across the top of the Bay and south to Williamstown, further west to Werribee.

Now though, almost five decades after its initial commission, it sits idle in a field back off the Richmond River, a single Hitachi EMU carriage (a Martin & King stainless steel), surrounded by swaying cane crop over from the Pacific Highway on the western side of Woodburn in northern New South Wales.

We find it online and book days there. The photos, aiming to show how it’s been converted and how comfortable and ‘left-of-centre’ it is as accommodation but still showing its rustic surrounds, remind us of time spent in the Deep South – reimagined places to stay set in wide and open spaces in rural Mississippi, places like here where hard work and dirty trucks, sweat-stained caps and faded flanno shirts define how it all works, the ease of time this carriage now offers a far cry from how real life unfolds about it.

Today, it no longer smells like hot brakes (dank rubber on shining steel discs), but takes on the olfactory hue of what’s happening in its place of dotage; hot cow shit in damp straw, wet earth under pomegranate trees, the perpetual aroma of cane syrup let loose via the sharp beaks of crows and the cockatoos that constantly forage the sweeping and swaying green-thick fields mere metres from the back doors, the doors that once disgorged weary commuters but that today see only happy travellers and those who want solitude, set nowhere with little company other than the cows, the crows, the long-legged sea-birds flown inland from the sea across the river and the way, ten clicks to Evans and the pounding surf beyond.

We park out the front, having navigated through the cane fields, unload and carry inside – food and a couple of bags of clothes, a pile of Addy’s books and a few of her stuffed guys, a pile of old newspapers to start the fire, a couple of bottles of good red, a bottle of single malt. No shoes allowed inside, so we kick them off and slide about the polished wood floors in our socks.

We potter about for a couple of hours, exploring the train, wandering down the edge of the house paddock to talk to the cows that mill about over the barbed wire fence down the bottom where the young fruit trees struggle in the hard earth, cracked and rigid from months with no rain.

It’s still green though, the grass thick, if sparse. We talk to the cows until it’s time to think about dinner. The cows ignore us co mpletely.

mpletely.

The clouds appear not to move and yet they’re obviously being blown to oblivion up high, stretched across the dying blue sky toward the encroaching black from the west. The breeze whips in and plays with the fire, pushing the deep orange flame high, wittering through it and snapping it to breaking point where it disappears and another forms in its place.

I feed it. Thick blocks from the yellow bag bought from the servo in Bruns for fifteen bucks the day I filled the truck with diesel in preparation for this exact moment.

It consumes greedily in the background as we do crosswords together and Addy eats cut sausage from the barbeque dipped in cheap tomato sauce and talks incessantly, bits of lettuce hanging from her young mouth, sauce staining the front of her old t-shirt.

I duck inside and come back out, a yellow tin in hand which I top off and sip from, the cold and wet beer staining the back of my throat with that happy soft burn and I smile at my little biscuit and ruffle her hair and she smiles up at me with her mouth bulging full.

Claire stretches her long legs across from chair to bench seat and picks up the Good Weekend magazine to find the quiz and Mum leans back and sips from her glass of sparkling wine, the setting sun highlighting the sheer volume of her grey and curly hair.

I stand and pace and poke the fire and look about, across the open spaces, listen to the throaty, deep burr of trucks gearing down as they come into town across the river, a sound which backs the myriad birdsong and the gentle lowing of cattle in the field adjacent.

It all feels like nothing but a quiet, gentle and strong contentment – where you’re perfectly at ease with little, in a place where there’s nothing, but in terms of now and then, you’ve brought with you everything.

It all feels like nothing but a quiet, gentle and strong contentment – where you’re perfectly at ease with little, in a place where there’s nothing, but in terms of now and then, you’ve brought with you everything.

Later, Addy asleep, we cook ours under the tin out the front, sausages on the barbeque, a heaping salad bowl in the middle of the table. I uncork a bottle of French pinot noir, an indulgence for the occasion.

Across the way, the cane harvest has been in full swing all day, brutal and unearthly looking machinery all whirring corkscrews and spinning blades that’d look more at home on the Fury Road than here, trucks on tank treads boiling the mud alongside catching the threshed fibres. The clanking has back-dropped the scene, along with the truck burr and the birdsong, the cattle low and the tiny chatter, for most of the evening.

And when it’s bare, when the field has been stripped, they burn the stubble.

And when it’s bare, when the field has been stripped, they burn the stubble.

From the dark springs a pyre. It starts low and orange but builds and blows up and out and turns an angry red, then orange again, then yellowing into the darkness of the night. It’s dry and hard and it crackles across the flat ground to where we’re standing, almost lit orange too against the glow which burns hard and fast and is gone almost before you can properly take it in.

The burning crew circle the field, keep it contained, make sure it dies along with what it’s killing then, into dust-coated trucks, they head across the river to the squat little tavern on the old highway and drink their weight in beer in celebration of a good day’s work.

We watch it all in the space of time it takes to cook our dinner.

***

Later still, as I pace around out the back by myself, doing laps of the decrepit pool table, a bent cue in one hand, an almost spent beer in the other, the heavens open. It’s gentle at first, a smattering on the tin over my head, but the low-slung cloud soon enough loosen their collective grey loins and a torrent is unleashed.

The water pools at the base of decking posts and around the wheels of the truck parked just past the steps, running thick rivulets down its off-white doors, cutting lines through the dust accumulated after only a day in the middle of nowhere.

It eases but stays all night, the next morning bringing no respite; Claire sits up in bed and pulls back the curtain and can see nothing across the wide fields but white and wet mist. We’re hemmed in and more than happy to accept it.

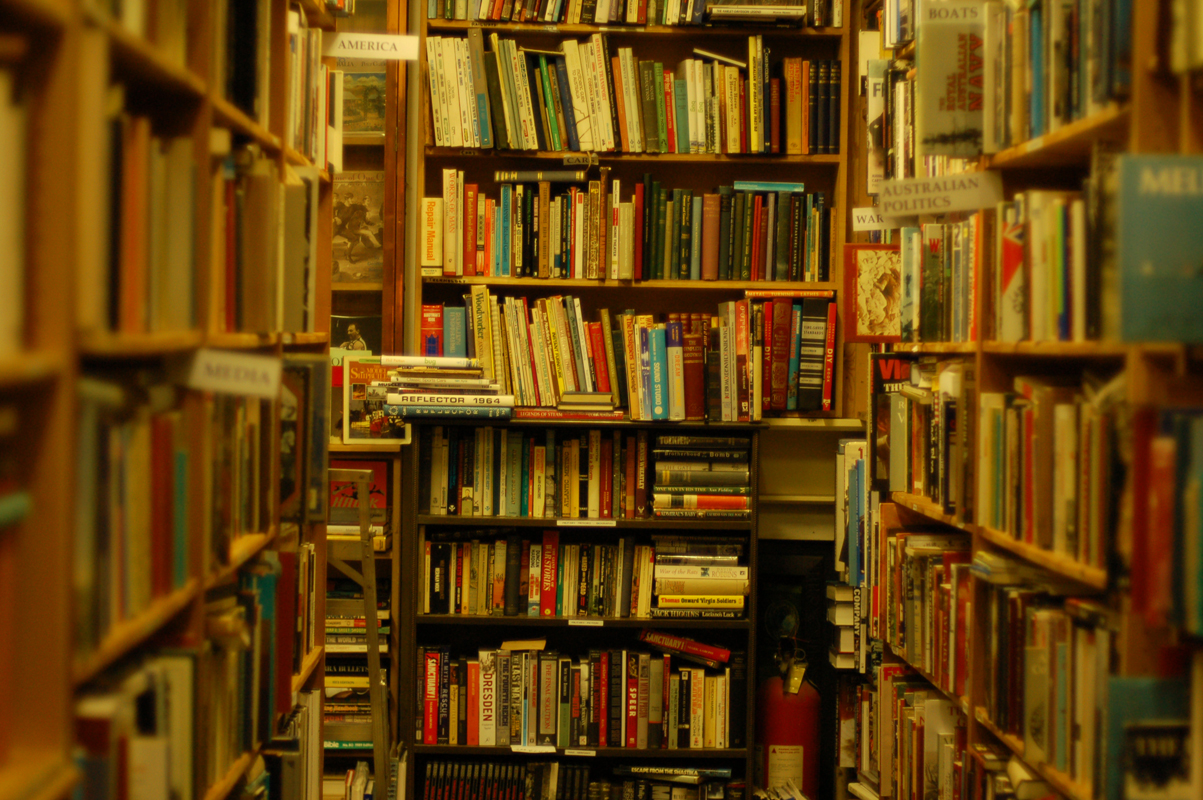

The day is whiled away reading newspapers and books, batting about loose balloons from the previous night’s festivities. Mum’s come down for the first night, and around lunchtime, she heads home.

I’d driven into town to buy the papers earlier, finding nothing in Woodburn and so heading into Evans, stopping at the IGA, which only stocked the Daily Telegraph, moving on to the newsagent on the main drag to find something worth spending my money on. I get soaked in only the few metres from door to door.

I run back out, heaving open the door and jumping in in a single motion, tucking the papers onto the dashboard and heading back to the train where the day is whiled away.

***

We stack raincoats in the back of the truck, along with a small bag full of water bottles and apples, a bag of chips and some loose muesli bars. Time is of no consequence. I realise, minutes out from Evans, as the sun finally bursts from behind thick and grey cloud, that I’ve forgotten my sunglasses, and so we swing right into a side road and u-turn and head back to get them.

There are kangaroos grazing off the side of the road, so we stop and pull in to look. They straighten, stopping mid-chew, regard us from behind impossibly long eyelashes. We stare at each other for ages.

A little way past the Golf Club, there’s a road called Blue Pool Drive, and so we head down there, in search of potential blue pools. There’s nothing but deep bush and heavily rutted dirt track, huge and muddy puddles which paint the white truck a filthy brown. We reach the end and find a Private Property sign. No matter, we u-turn again and head back.

Time is of no consequence.

We end up, the three of us, on Chinaman’s Beach. The world is grey and blustery, but it’s fresh and the salt smell fills us to the brim. The sand is hard packed and pockmarked with the rain just gone. Addy finds a pelican feather and carries like in her little fist like it’s the most valuable thing on earth.

The wind whips us from front on. Her golden curls catch it and fly behind her. Her jacket, the lining of it, is pink. Her hair and the pink lining are lit bright on the low-colour scene, she runs past me and looks up at me and her eye-lashes and eyebrows are vivid in contrast to the comparative dullness of everything around her. She glows naturally.

The wind whips us from front on. Her golden curls catch it and fly behind her. Her jacket, the lining of it, is pink. Her hair and the pink lining are lit bright on the low-colour scene, she runs past me and looks up at me and her eye-lashes and eyebrows are vivid in contrast to the comparative dullness of everything around her. She glows naturally.

I turn to see where Claire is, and find her just behind my left shoulder. She smiles and she glows too.

As we round the rocky outcrop at the end of Chinaman’s, crossing onto New Zealand Beach, the headland rises dramatically, a small but sheer sandstone cliff writ red with white and off-yellow streaks, towering above us, bright against the grey sky.

We find a cave set into the rock, just back of the water line and dripping but with enough dry spots in which to sit. We open the bag and eat chips and an apple each, eventually tossing the spent cores into the ever-surging ocean. Low tide but eternally hungry. They wash away before we can even count to ten.

Addy runs down the sand, finds a tall rock in the middle of it all and asks me to help her climb it. Claire takes a photo and we’re in silhouette against the tempestuous sky, climbing what would seem like, for Addy, an almost insurmountable peak. I swing her off of it, around in circles, and almost drop her to the wet sand as she laughs and wants to do it again.

We get to Snapper Rock as it starts to rain again, and we huddle under a low rocky shelf and eat the strawberries. Above us, Pandanus Palms have rooted in the impossible earth and their huge and knobbly pods have dropped on the beach. I whip one into the water, it hits a rock and bounces back, neither broken in the slightest.

Walking back, we take the inland track, back off the beach, unsigned, a goat track worn into the scrubby grass to white sand, veering north and up onto the headland, a plateau of sorts that extends as far as we can see, nothing growing higher than a metre but the vegetation thick and unyielding – I say to Claire it’d be a desert scene if not for the fact it was verdant from rain and rain, we need to push through sopping boughs and prickly branches which wet our jeans and, as we crest it all, up the top with nothing to protect us, the rains come again, sliding in fast and angular, blown by unseen wind, wetting us all the more and we run, squealing, laughing, cursing the timing. My jeans are soaked through.

Addy stops in front of me, forcing me to pull up short, to pick a single purple flower, the rain and wet of no consequence to her at all.

We step, eventually, out of a thicket into the carpark. A sudden emergence. It’s full now, it was just us a couple of hours ago, and the truck is there, glistening under wet mud. We jump in, turn the heater on, head back to the train, sharing the last of the chips as we drive.

***

That night, heading home tomorrow morning, as if to finish it off properly, as the footy winds down and the whisky supply dries up, the wind whips in and drives a last bit of rain sideways under the flimsy roof, moving me closer to the weather-board walls, zipped up with arms folded against the cold but loose and happy to bed down within the old train’s steel walls, no longer rattling death but somewhere in nowhere to take stock and slow down, surrounded by the cane stubble and truck burr across the river.

The days have seemed endless, and righteously so.

There’s another apartment building off to the edge of this lot, old and crumbling, burnt light brown by the hovering sun, squatting broke and deprived in stark contrast to the statuesque highrises that reflect the sun back into your face. A faded name plate proclaims them to be the San Miguel Apartments; the four balconies are bare, save for the bottom right which sports an ice bucket on its ledge, emblazoned with the logo for Corona beer, a small and spiky cactus poking above its silvery rim the only piece of greenery visible in an otherwise brown and deadened façade.

There’s another apartment building off to the edge of this lot, old and crumbling, burnt light brown by the hovering sun, squatting broke and deprived in stark contrast to the statuesque highrises that reflect the sun back into your face. A faded name plate proclaims them to be the San Miguel Apartments; the four balconies are bare, save for the bottom right which sports an ice bucket on its ledge, emblazoned with the logo for Corona beer, a small and spiky cactus poking above its silvery rim the only piece of greenery visible in an otherwise brown and deadened façade.

mpletely.

mpletely. It all feels like nothing but a quiet, gentle and strong contentment – where you’re perfectly at ease with little, in a place where there’s nothing, but in terms of now and then, you’ve brought with you everything.

It all feels like nothing but a quiet, gentle and strong contentment – where you’re perfectly at ease with little, in a place where there’s nothing, but in terms of now and then, you’ve brought with you everything. And when it’s bare, when the field has been stripped, they burn the stubble.

And when it’s bare, when the field has been stripped, they burn the stubble. The wind whips us from front on. Her golden curls catch it and fly behind her. Her jacket, the lining of it, is pink. Her hair and the pink lining are lit bright on the low-colour scene, she runs past me and looks up at me and her eye-lashes and eyebrows are vivid in contrast to the comparative dullness of everything around her. She glows naturally.

The wind whips us from front on. Her golden curls catch it and fly behind her. Her jacket, the lining of it, is pink. Her hair and the pink lining are lit bright on the low-colour scene, she runs past me and looks up at me and her eye-lashes and eyebrows are vivid in contrast to the comparative dullness of everything around her. She glows naturally.