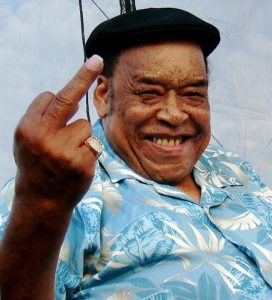

James Henry Cotton died on Thursday March 16, in Austin, Texas. He was 81, and while perhaps unknown to people not familiar with the blues, the man was a behemoth – a working musician by the time he was nine, he cut his teeth under Sonny Boy Williamson II, before branching out and recording with the great Howlin’ Wolf for Sun Records. Then, as a 20-year-old, he joined Muddy Waters’ band, where he stayed for a decade or so, before moving out solo – a legend of blues harmonica, Cotton recorded a slew of albums under his own name over the years, and was still touring three years ago when he made his first trip to Australia.

James Henry Cotton died on Thursday March 16, in Austin, Texas. He was 81, and while perhaps unknown to people not familiar with the blues, the man was a behemoth – a working musician by the time he was nine, he cut his teeth under Sonny Boy Williamson II, before branching out and recording with the great Howlin’ Wolf for Sun Records. Then, as a 20-year-old, he joined Muddy Waters’ band, where he stayed for a decade or so, before moving out solo – a legend of blues harmonica, Cotton recorded a slew of albums under his own name over the years, and was still touring three years ago when he made his first trip to Australia.

I was fortunate enough to interview him in 2013 for a story about him and his work for a Sun Records special issue of Rhythms magazine. The brief Q&A style yarn is reproduced below…

Cotton Mouth Man

Harmonica legend James Cotton, whose career is still as strong as ever, looks back at his years with Sun Records.

By Samuel J. Fell

Harmonica legend James Cotton, perhaps the last surviving blues player who recorded with Sun Records, was born in Mississippi in 1934. He grew up on a cotton plantation, working the fields, but soon became all consumed by the blues he heard on the radio. He took his harp and was soon making money as a busker, before leaving home and joining Sonny Boy Williamson’s band, taking over as leader when Williamson left.

This was short-lived, and soon Cotton was driving a dump truck. It wasn’t long before he got back into music though, moving to West Memphis and hooking up with the likes of Little Junior Parker, BB King and Howlin’ Wolf, with whom he recorded his first Sun session. From there, his career began in earnest, he played in Muddy Waters’ band for a decade or so, and is still making records today. Cotton himself takes over the story, filling in the gaps:

Your mother gave you a harmonica for your sixth birthday, which you began to play, but it wasn’t until you heard King Biscuit Time on the radio that you realised the instrument could be played a completely different way – the way of the blues. Do you remember how you felt when you first heard that music? How did it make you feel? What was the connection like?

It put something inside of me, something I can’t name, and it made me feel really, really good. I’d never heard anything like that. I’ve never forgotten that moment. I realise now it connected me to the outside world, got me off the plantation and connected me to people all over the world. I never even dreamed that could be possible. My whole world then was the Bonnie Blue plantation, and the field work we all had to do. My mother took me to the field and showed me how to pick cotton when I was about four years old.

Your first recorded session was with Howlin’ Wolf in 1952, not long after you’d moved to West Memphis – how did you hook up with The Wolf? What was he like to play with? What are your memories of that session?

Howlin’ Wolf heard me play with Sonny Boy Williamson’s (Rice Miller) band. Since we both played harp, Sonny Boy and I never played at the same time with his band. In the middle of his set he’d call me up to play. I’d play a few songs, leave the stage, and he’d come back and finish his set. Wolf was a very nice guy to play with. He was a warm, decent man but I didn’t want to mess up his music or he’d let me know I did!

I remember he’d say, “Man, I want my music right. If you don’t play my music right, I’m gonna have t’let ya go.” He never had to. My memory of my first session at Sun Records with The Wolf, is I had never really ever heard my music played back. I always heard it out of an amp when I was playing it [but] I never heard it recorded before. It scared me! I was 13 years old and very, very country. I heard everything I was playing. Heard all the mistakes – and all the good parts I played, I heard that, too. I played harp for The Wolf on ‘Moanin’ At Midnight’. He played harp on ‘How Many More Years’. Those songs were released back to back on one single record. Both songs became hits.

It was that session that brought you to the attention of a young Sam Phillips, who then contacted you about making some records – tell me about your first meeting with Sam.

When I walked into Sun Records, Sam Phillips shook my hand and asked me if I had any of my own songs. At this time I had ‘Cotton Crop Blues’, ‘Hold Me In Your Arms’, ‘My Baby’, and ‘Straighten Up Baby’. He said he wanted to hear them. He recorded them straight away. Here’s how it came down – my drummer, John Bowers, didn’t show up, so I ended up playing drums. I looked around the studio. There was one bass drum and a 10-inch cymbal. I needed a snare, so I grabbed a 51 Goldcrest beer box made out of cardboard, turned it upside down and went to work. That’s why there’s no harp on any of the four sides. Pat Hare was on guitar. That was the original recording. Later, Sam Phillips added piano, bass, and horns. He might have added a drummer, too.

After your first session for Sun, recording with Willie Nix, you began cutting your own records with Sam Phillips – what was he like to work with? He’s got quite a reputation for letting the artist play what they want to play, for keeping it real, for keeping the blues pure – was that the case?

Working with Sam Phillips was all right because he let me play like I wanted to. I remember him asking me to do just two things differently. One time he asked me to make a song longer, which I did. I wasn’t a drummer and here I was playing a session for the first time and I dropped time. Sam heard that and asked me to do that again. Other than that, he didn’t say much. We were both so new at what we were doing, it was still strange to us, we were both feeling our way – we’re talking about recording these songs 63 years ago. We both had different dreams about this music, the blues, and, looking back on it, both our dreams came true.

Back in the ‘50s, when segregation was is full swing, Phillips didn’t seem fazed by that – it seems that to him, colour didn’t matter, it was all about the music and the people who played it, whether they were black or white. What was it like, as an African American artist, to have a place to record where race played no part, and you were free to do what you were made to do?

It was a really good feeling. Sam Phillips’ Sun Records was my very first studio. It was good to be free, respected, and accepted, both me and my music, by a white man. But I knew the second I walked out the studio door, I knew it would be the same racist world that I lived in, that was just the way it was, what I was born into. I’m thankful the world has changed, I’ve seen so much change for the better. Better for the music and better for me, too, and that’s the truth. Now it makes me feel that all the bumps and bruises was worth it.

Of course, after you cut those tracks with Sun, you hooked up with Muddy Waters and played in his band for over a decade, which is a whole other story! Focusing on Sun though, looking back, how important was what Sam Phillips was doing? How important for the blues was his work, was Sun Records?

It was very important, not only to me, but what Sam did for music history. The four songs I recorded got me out of the cotton fields and made me known to the people as a real musician, even though I just a kid. Real musicians make records. I recorded at Sun Records before Elvis, Carl Perkins and Jerry Lee Lewis. We all know the Sam Phillips story and what he did with that little record company and his big dream. Sam started with the blues. Willie Dixon nailed it, “The blues had a baby and they named it rock ‘n’ roll.” That’s what Sam did.

You’re one of the (if not the) last remaining blues artists who recorded on Sun – you must be immensely proud of not only what the label was able to achieve, but what you were able to achieve during those years (not to mention the years until now).

Of course, I feel good to still be around. And I’ve enjoyed every minute of my career. I started out a little boy wearing overalls, walking barefoot down a dirt road, blowing my harp. I’ve traveled the world with my harp over and over and I’m so thankful for that. Life has been good to me. My fans are part of my family, I mean that. I have played many countries, but one I have not played is Australia. I know this is an Australian magazine, I’d like to play for the people of Australia.

Just lastly, you’re about to release a new album on Alligator Records, which is fantastic – as Bruce Iglauer (Alligator) says, how many Sun artists from 1954 are still recording? Tell me briefly about this new release – how does an artist like yourself, who’s been making blues records for over fifty years, go about doing so in 2013? And for the sake of comparison, what’s it like making a record today, compared to back in 1954 at Sun?

Well, the first thing is there wasn’t a 51 Goldcrest beer box turned upside down for a snare drum on my new CD, Cotton Mouth Man! Nowadays, recording is technically much easier, but that doesn’t change my feeling for the music. That’s what it is all about, feeling. If I don’t feel it, I can’t play it. I’m serious about that.

Cotton Mouth Man is very different from any other record I’ve ever made, it’s got lots of new songs we wrote about my life. I even wrote one about Bonnie Blue, the plantation I grew up on in Mississippi. All the songs are originals except for one. I think people will learn a lot about my life when they listen to the words. I wrote liner notes for it too, telling people how we came about making it and thanking everyone who helped me put it together.

My producer is Tom Hambridge, who also played drums. Some of my favorite musicians and singers are the guests: Gregg Allman, Joe Bonamassa, Ruthie Foster, Warren Haynes, Delbert McClinton and Keb’ Mo’. We’ve got Chuck Leavell on keyboards and Colin Linden on Resonator. We also had Rob McNelley on guitar, Glenn Worf on upright bass, and Tommy McDonald on bass. My band members, who’ve been with me for many years now – singer Darrell Nulisch, Tom Holland on guitar, Noel Neal on bass, and Jerry Porter on drums – are on the record too. I was fortunate to have all these good people who are great musicians, come together to make this record with me. I hope everyone who listens to it feels it. I know I sure did!

Cotton Mouth Man is available through Alligator Records.