[Published in Good Weekend magazine, April 14 2018]

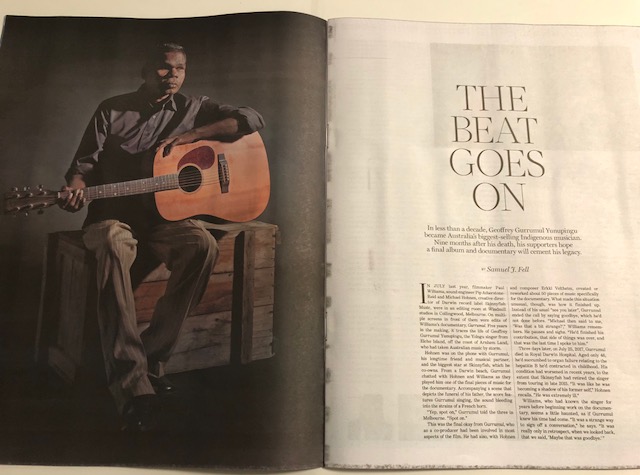

In July last year, filmmaker Paul Williams, sound engineer Pip Atherstone-Reid and Skinnyfish Music’s creative director Michael Hohnen were ensconced in an editing room at Windmill Studios in the Melbourne suburb of Collingwood. On multiple screens in front of them were the edits of Williams’s documentary, Gurrumul. Five years in the making, it traced the life of Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu, the Yolngu singer from Elcho Island 500km off the coast of Darwin who had, in the previous decade, taken the music world by storm.

Hohnen was on the phone with Gurrumul, his longtime friend and musical partner, and the biggest star in the Skinnyfish stable, a Darwin-based record label founded and co-owned by Hohnen. From a Darwin beach, Gurrumul chatted with Hohnen and Williams as they played him back one of the final musical pieces to be included in the documentary. Accompanying a scene towards the end of the film that depicts the funeral of his father, the score features Gurrumul singing, the sound bleeding into the strains of a French horn.

“Yep, spot on,” Gurrumul told the three in Melbourne. “Spot on.”

This was the final OK from Gurrumul, who as a co-producer had been active in most aspects of the film, and along with Hohnen and Melbourne-based composer Erkki Veltheim, had created, or reworked, about 50 original pieces of music specifically for the documentary.

What made this situation unusual though, was how it finished up. Instead of his usual “see you later”, Gurrumul ended the phone call by saying goodbye, something he’d not done before. “It happened in a way, that Michael then said to me, ‘Was that a bit strange?’,” Williams remembers. He pauses and sighs. “He’d finished his contribution, that side of things was over, and yeah… that was the last time I spoke to him.”

Three days later, on July 25, 2017, Gurrumul died in Royal Darwin Hospital. Aged only 46, he’d succumbed to organ failure relating to the hepatitis B he’d had since childhood. His condition had worsened in recent years, to the extent that Skinnyfish had retired the singer from touring in late 2015. “It was like he was becoming a shadow of his former self,” Hohnen recalls of the time. “He was extremely ill.”

Williams, who had known the singer for a number of years before beginning work on the documentary, seems a little haunted, like he thinks perhaps Gurrumul knew his time had come. “It was a strange way [for him] to sign off a conversation,” he says. “It was really only in retrospect, when we looked back, that we said, maybe that was goodbye.”

***

At the time of his death, Gurrumul was the highest selling indigenous musician in Australian history, a title he still holds. His eponymous 2008 solo debut was certified three times platinum in Australia, and appeared in top 20 album charts in Belgium, Germany and Switzerland upon its European release the following year. His second album, Rrakala (2011), made some small inroads into the American market, a notoriously tough market to crack, an attempt ultimately thwarted by his premature death.

His third release, The Gospel Album (2015), cemented what those close to him had known for years but others were only just beginning to realise – that this unassuming indigenous Australian, who was born blind and taught himself to play the guitar upside down, wasn’t merely an angelic voiced flash-in-the pan.

Yesterday, April 13, Gurrumul posthumously added one final album to his canon. Djarimirri (Child Of The Rainbow) has been more than six years in the making and involves the singer, in Hohnen’s words, delving “deeper into the cultural elements of his music”. Preceding the release of Williams’s documentary by a couple of weeks (the film will be released on April 25), Djarimirri stands as the singer’s final gift to the world, one last reminder that his rise to fame was more than deserved.

***

While his rise may have seemed meteoric, Gurrumul paid his dues, a slow build that began with culture-bridging group Yothu Yindi in the 1990s. He played a number of instruments and contributed backing vocals to four of the band’s six albums, most notably its breakthrough 1991 release, Tribal Voice, and with Manuel Dhurrkay, fronted Saltwater Band, releasing three records with this group in the decade from 1999. By the time Skinnyfish came to release the eponymous Gurrumul in 2008, the man and his music were match fit.

“Gurrumul toured the world before he was Gurrumul,” notes hip hop artist Adam Briggs, with whom Gurrumul collaborated in 2014 on the song ‘The Hunt’, from Briggs’s second full-length solo album, Sheplife. To Briggs’s mind, Gurrumul’s popularity was testament to his hard work, his musicality and his talent. “People forget he was in Yothu Yindi and Saltwater… so by the time he was Gurrumul, he was ready.”

Legendary producer Quincy Jones has noted of the singer, “this is one of the most unusual and emotional and musical voices that I’ve ever heard”. It wasn’t just Jones – Sting, will.i.am, Elton John, Stevie Wonder and Australians Peter Garrett and Paul Kelly all count among the singer’s admirers. In garnering fans like these, Gurrumul sold out venues the world over, won awards, and confounded critics with his wide-ranging success within the western world.

“He was special in so many ways, in western and Yolngu worlds,” his niece, Miriam Yirrininba Dhurrkay, tells me. “He was writing these songs and … the words just come into his mind and heart, and even though he couldn’t see the nature, he was born to, you know, feel the nature.” To see without seeing. “Yeah. He had a special place to see, which was his heart.”

It was his heart that eventually gave out, having battled on through the liver and kidney failure relating to the existing hepatitis B. Dialysis was deemed the only option in combating his condition, but Gurrumul, who’d been admitted to the ICU department at Royal Darwin Hospital seven times in the year leading up to his death, was refusing treatment.

“Dialysis was not something that he enjoyed,” Hohnen says. “He basically, in the end, I believe, chose to not go on dialysis, not stay on it. And you don’t really have any options – it’s dialysis or nothing.”

***

Djarimirri is, essentially, an album that showcases ancient Yolngu chants, setting them against an orchestral background in order to make them sonically palatable to the western ear. Gurrumul was no stranger to orchestral work, having released in 2013 an entire live album accompanied by the Sydney Symphony. Where Djarimirri is different though, is in its minimalist orchestral traditions; Hohnen cites the likes of Michael Nyman, Steve Reich, Arvo Part and Phillip Glass as influences.

These Yolngu songs, some estimated at more than 4000 years old, were traditionally backed by the didgeridoo, or yidaki, repetitive rhythms that gave the lyrics a foundation from which to build. The trick with Djarimirri, was in replicating these sonic patterns on western instruments, while still leaving them recognisable to Yolngu people.

“Michael had this concept of combining the more traditional songs and chanting and yidaki patterns, with this kind of contemporary minimalist orchestral tradition,” confirms Erkki Veltheim, the Melbourne-based composer and violinist who helmed the album, and had played with Gurrumul on a number of occasions over the previous decade.

“At first I was kind of trying to turn it in my brain, trying to figure out how these different traditions could work together, but then the more I thought about it, the more it actually made sense because of the very nature of these traditional songs and the yidaki patterns, which kind of do have a lot of repetition in them, but also a lot of variation within that repetition, [which combines] really well with the orchestral minimalist tradition.”

Veltheim started listening to the recordings of songs Gurrumul had already made back on Elcho. From there, the task was to find instrumental transcriptions of the yidaki patterns and transcribe them into a western notation, to be played on western instruments.

“[That] was a real challenge, but also a great pleasure to come up with these arrangements,” he recalls. “And the most nerve-wracking thing for me, was whether Gurrumul himself and his family and the other people on Elcho would actually relate to these arrangements…. that was the key. The important thing [was] that every step of the process, we’ve made sure that we haven’t done anything that doesn’t communicate those songs.”

The 12 songs that make up Djarimirri all relate to specific totems and aspects of Yolngu culture – Waak (Crow) in E-Flat Major, Ngarrpiya (Octopus) in A-Flat Major, Gapu (Freshwater) in D Major, Baru (Saltwater Crocodile) in E-Flat Major, Marrayarr (Flag) in F-Sharp Major, to name a few. All songs ended up in major keys, a coincidence, which to Hohnen’s mind gives it a happy vibe.

Initially, Djarimirri isn’t an easy listen. It relies heavily on repetition, and Yolngu songs are traditionally quite short, so Gurrumul’s vocal contributions are fleeting. Repeat listens begin to cast new light on what’s happening though – there’s variation within the repetition, and the drone of the strings, the popping of horns, add their own weight to what is, within each song, a slow building story. The purity of the singer’s voice across this sonic soundscape tops it off.

Djarimirri is essentially an exercise in ethnomusicology – the keeping alive of this ancient music, albeit in a more modern fashion, so that those yet to come are able to access it, no matter their cultural background. “[Gurrumul had] hundreds of songs in his head,” says Hohnen. “He wasn’t writing a lot of new contemporary style songs but he probably [knew] 400 or 500 songs, traditionally.”

***

Completed early in 2017, the album was being prepared for release in the middle of that year. When Gurrumul died, they re-thought it, in part due to the fact that in Yolngu culture, when a member dies, their name, image and any music or art is retired.

“[We] held it for a year,” Hohnen confirms. “It would just not have been right to put it out. Although, spending a lot of time with the family, they sort of said to us, even at his funeral, no one’s stopped listening to his music, [they] all play it.”

In the press pack sent out with the advance stream of Djarimirri, there’s a note on the use of his image and name which reads, in part, “The family have given permission that, following the final funeral ceremony (which occurred at Galiwin’ku on Elcho Island on November 24 last year), his name and image may once again be used publicly, to ensure that his legacy will continue to inspire both his people and Australians more broadly.”

“In most situations when an aboriginal person up here passes away, the name gets changed, and the music and imagery gets stopped,” explains Hohnen, “[but] it’s hard when someone’s as famous as this. I think it’s more they’re really proud… and I think Yolngu don’t want him forgotten, that’s what they said to us. There’s this ownership of him being a public representation as well.”

When we speak, Hohnen is just pulling himself back together after what he describes as a fairly dysfunctional six months. “It’s affected Mark and I very personally,” he says, of his co-founder at Skinnyfish Music, Mark Grose, “because [Gurrumul] was such a unique and happy person, someone who, no matter how recalcitrant, always made you feel that fun and music and life and traditional culture was here to be lived and loved.”

Gurrumul was Skinnyfish Music’s biggest artist, and his success enabled the label to expand and focus on other acts like Caity Baker and The Lonely Boys. Royalties from Djarimirri will flow, in part, into the Gurrumul Yunupingu Foundation, which will us the money to “create greater opportunities for remote Indigenous young people to realise their full potential and contribute to culturally vibrant and sustainable communities”.

It’s not lost on anyone involved with the making of the record how sad it is that its main player won’t be here to see it out into the world. “We wanted to release the album while he was alive so he cold live it out on the airwaves around his community and further afield,” says Hohnen. “But I now feel like we did everything possible to live up to the standards that he and his family expected of us. The recording is as much a representation of all Yolngu.”

This is what Djarimirri is primarily about – legacy. “There’s different ways people can go about activism,” Hohnen continues. “There’s anger, abuse, there’s hurt, there’s quite sinister ways, destructive ways. The journey that we took with him was almost the opposite. And, for me, his legacy was opening people’s hearts to one of the greatest assets of this country.”

Briggs, who became a friend of Gurrumul’s in the years after their 2014 collaboration, agrees. “This last record… is testament to him transcending genre and transcending what’s expected of an indigenous artist . This album is an orchestral piece, so it’s sheet music… it could be read by a conductor or composer in Germany, and they’d understand it. It transcends cultural barriers, because music is an international language. Anyone will be able to read this, and translate it and play it. Even in his death, he’s transcended genres and cultural barriers. Him and Michael, they’ve delivered this gift of music.”

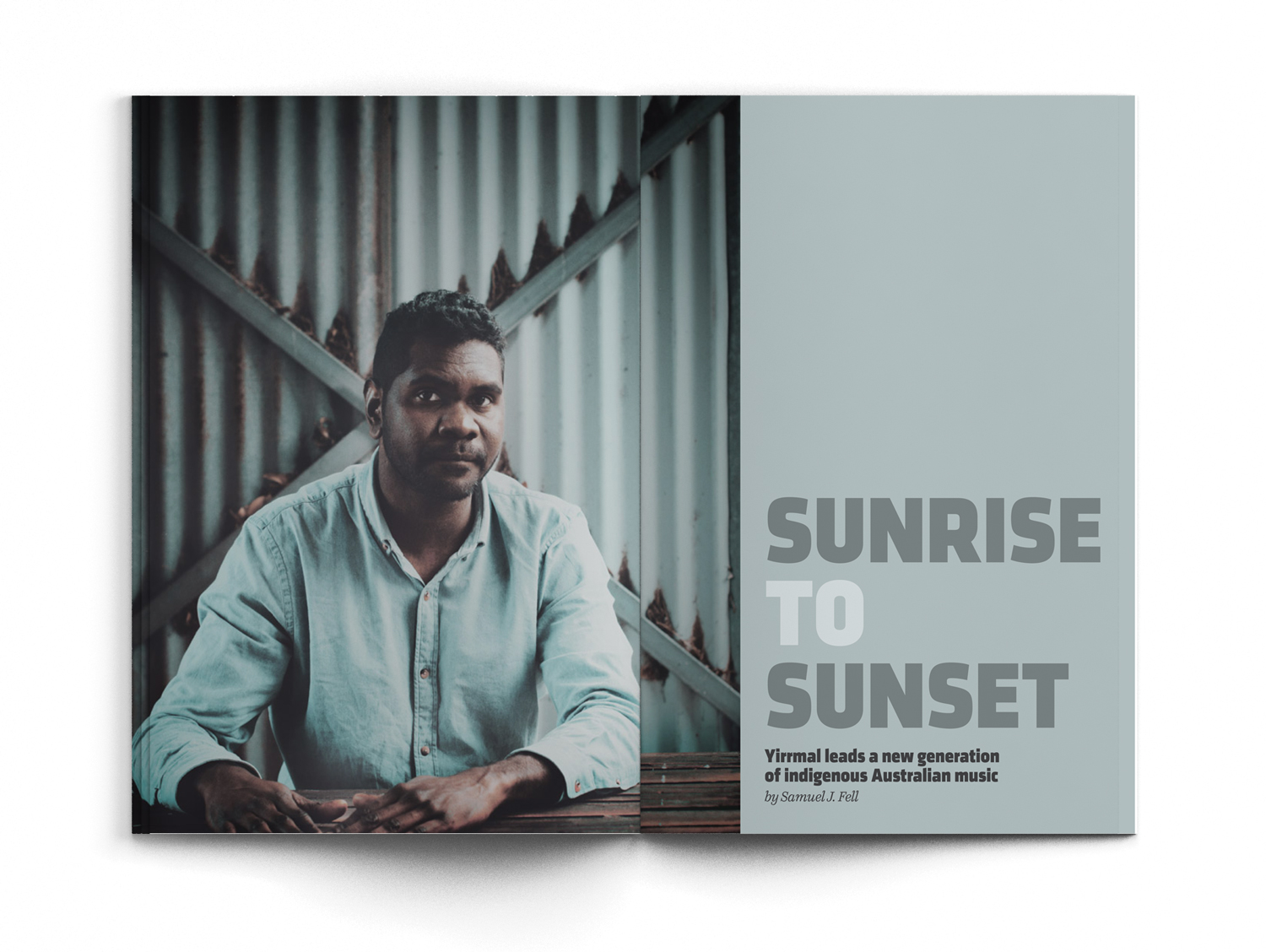

Gurrumul’s niece says his life and music are still inspiring young Yolngu people. “A lot of youngsters in the north-east Arnhem land region, where G comes from, and other youngsters from all around NT, from every aboriginal community… a lot of youngsters are doing music today. Most of the young people I know, they want to continue his legacy, they want to show the world that they can do it… if he can do it, why can’t we do it, you know?”