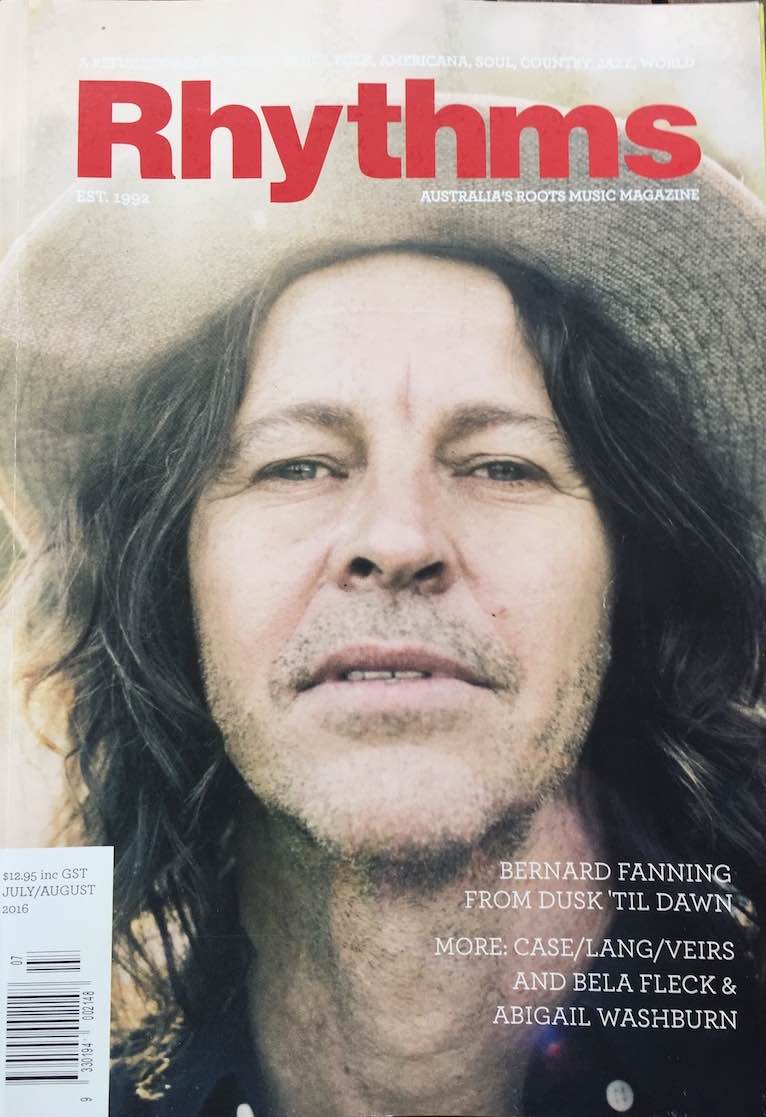

[Published in the July/August issue of Rhythms magazine, Cover Feature, July/August 2016]

While BERNARD FANNING’s new album stems from a feeling of unease, it blooms as one of the songwriter’s strongest releases. He talks to Samuel J. Fell.

It’s a Monday afternoon. Late autumn and sunny. It’s crystal clear and the air is sharp, cool in the shade courtesy of a light breeze but warm in the sun, brightening the scene; makes the grass seem greener and the surrounding shrubs livelier despite the fact there’s been no rain for a month or so.

Bernard Fanning sits on a day bed, leaning against the wall of his small studio, up on a hill above Byron Bay. You can see it down below, spread along the coastline in among the trees against the water’s edge. Out in the bay itself is Julian Rocks. It’s so clear you can see the whitewater breaking around their base. The lighthouse sits atop Cape Byron, slightly to the south, the sunlight glinting off its tall, white walls, standing guard over the most easterly point in Australia.

Fanning sits taking it all in. It is, as I’d mentioned to him when I’d first arrived, a view you’d not get sick of. He agrees and during the couple of hours we spend sitting out here, we both periodically gaze out over it all. It’s calming. Serene. Seems to me to be a perfect place to put together a record.

Fanning, in light blue jeans and black jacket, hair hanging down to his shoulders, flipping across his face, grey stubble, pale skin, is in good spirits. He smiles a lot and his laugh rings out across the green, sloping garden, occasionally startling lorikeets playing in the trees hanging over the driveway to the side. I’m always wary prior to speaking to prominent rock stars, well aware they could be completely consumed by an inflated sense of self-importance, nothing more than preening posers.

But Bernard Fanning’s not like that. Sure, he’s a prominent rock star, he fronted one of the most iconic Australian bands of all time in Powderfinger. His solo debut, Tea & Sympathy, was incredibly successful, five-times platinum. But he’s just a guy with a wife and kids, sitting here having a chat about music, about the state of the world, life in general. Just shooting the breeze like any of us.

Inside the studio, producer Nick DiDia is tinkering. Occasionally, music drifts out from the open door around the corner, soundtracking certain parts of our conversation. “It’s shit, isn’t it,” Fanning says at one point as he looks out across the Pacific. He laughs again. I do too as I follow his gaze. “Yeah,” I say. “Terrible.”

***

Bernard Fanning’s new album, his third solo effort, is Civil Dusk. It’s the first in a two-part series, the next being Brutal Dawn, slated for release sometime next year. Civil Dusk was written in part in Kingscliff, a small coastal village a little further north, and partly in Madrid, Spain, where his wife is from. It was all recorded here, aside from the demos, in this little space on top of a hill overlooking Byron.

“Civil Dusk, the term actually comes from civil twilight, which is a photography term,” he tells me. “It’s when the sun has gone down beneath the horizon. Scientifically, I think it’s when the sun is six degrees below the horizon. But pretty much everything is still visible, but not in direct light. And it looks different. So that idea, that metaphor…”

“Civil Dusk, the term actually comes from civil twilight, which is a photography term,” he tells me. “It’s when the sun has gone down beneath the horizon. Scientifically, I think it’s when the sun is six degrees below the horizon. But pretty much everything is still visible, but not in direct light. And it looks different. So that idea, that metaphor…”

He trails off at the end of that sentence and switches focus to the term brutal dawn, which we both agree is the perfect name for an album by a Norwegian death metal band, but the sentiment is clear. Civil Dusk is about things not being quite as they seem, or quite as you remember them, and they’re about to change. Perhaps to be revealed once more, in a different light later on, under a brutal dawn.

I ask him if, as a person, he’s a worrier, if he’s prone to anxiety. “Oh yeah, totally, I’m a real worrier,” he says candidly. The reason I ask this is because in the bio that accompanies the new record, he’s quoted as saying, “Each day, I wake with a feeling of unease.” It’s a line which ties in with the idea behind the record, the civil dusk preceding a brutal dawn.

“Yeah, doesn’t everyone?” he asks with a laugh when I read that quote back to him. “It sounds a little too depressing. I don’t mean… it’s unease, it’s not full-blown anxiety. It’s more like, I’ve got shit to do, lots to do. As an artist and a human being. Firstly as a dad, the basic stuff of making breakfast, getting school lunches ready, you know. Making sure everyone’s got two shoes on when they leave.

“[But] it’s a combination of everything. When I’m writing, I don’t sleep very much. I wake up a lot of times at night, and often with the last idea I had before I went to bed, kinda ringing in my head. And it’s pretty annoying, and pretty annoying for my wife. It’s hard to shake when you have an idea that you haven’t abandoned yet, that you haven’t managed to go, ‘I’m not gonna keep going’.

“And what I mean by that, that’s a completed song as well. It’s not like, ‘That song’s finished’, it’s ‘I’m not working on that anymore’. Because inevitably, a few months later, you’re gonna find holes in that idea and go, ‘Fuck, I wish I’d done that’.”

I venture that this is the lot of the artist, that no matter what you do, you’ll never really be satisfied. Or at least you’ll think you’re satisfied, only to realise a little while later that you no longer are. “Yeah, that’s exactly right. You have this momentary satisfaction,” he says. “Anyway, the anxiety thing, I don’t want to play that up too much… it’s more because I usually get up first in the house, at around 4:30, and I read the paper. And that usually starts that feeling of unease, just reading about the state of the world.

“And that impacts a lot on the way that I write.”

Despite this assertion, Civil Dusk isn’t a record populated with songs dealing with literal world events. It’s not an album that bemoans the state of the world, not in a direct sense anyway – Bernard Fanning, who in the past has been very vocal about, and supportive of, a number of pertinent social issues, isn’t setting out to preach to a world he sees as wrong, or broken. Civil Dusk seems to be more about a feeling and a state of being, as opposed to presenting like a list of injustices, set to song.

As well, these feelings are framed through a series of love songs, whether happy or sad, disguised somewhat – the meanings are visible, but not in direct light, the songs civil dusks in themselves.

Another strong thematic vein that runs through the record is the idea of decisions and their resulting consequences. “I guess that’s another symptom of age and being forty-something,” he muses. “Looking at decisions I made when I was in my 20s and things that I thought were a great idea at the time. I mean, I’m in the unfortunate position… of having a lot of the things I’ve said, recorded, when I was in my 20s and maybe not at my smartest.”

He laughs again. “So, things like that. But also looking at that in the wider sense, how are things like, even on a personal basis especially, Powderfinger breaking up, how that has impacted on me and other people around me, stuff like that.”

“I don’t really want to be drilling down into the detail of what the songs are about, because I don’t really like doing that,” he then says, changing position on the day bed. “I want people to have their own discovery of songs, they have that thing where they… it’s what I do, put myself in the position of the author, pretty much all the time, when I’m listening to music.

“If I can really relate to it, then I can sing that song with a real kind of verve, it resonates with me. Otherwise, it doesn’t really impact… I like people having the opportunity to do that themselves, without it being all explained and spelt out to them. I mean, you don’t really need to do it anyway.”

“The future’s suffocating on an echo from the past.” A line from ‘Belly Of The Beast’, the final song on Civil Dusk. One could interpret that in myriad different ways. It’s a strong line though, one of the strongest on the album. It sums up the civil dusk, the decisions and resulting consequence. It’s powerful.

Fanning laughs again, and I sip from my cup of coffee which is cold now, and light a cigarette, moving over to a sunny patch on the grass. We both look out over the ocean and we’re silent for a bit.

***

“All I knew is that I wanted to base it around acoustic guitars and pianos, that’s all I knew,” he says when I ask him what his initial MO was for Civil Dusk. “Whether I had a band or not, I didn’t know, and then I soon found out I’m not an accomplished enough musician to do a guitar and vocal record that would stand the test of time.

“I wanted to do most of it myself, I wanted to play most of it myself, which is kind of… Departures was the opposite of Tea & Sympathy, and now Civil Dusk and Brutal Dawn are the opposite of Departures. They’re reactions to what you’ve done before. And also stepping stones, I don’t know, it’s hard to explain.”

I suggest that despite how different this new album is to Departures, his second solo record which came after 2005’s Tea & Sympathy, to him it would no doubt seem a natural evolution. “Yeah,” he concurs. “Totally. But at the same time, I can understand why some people when they heard ‘Battleships’ for example, were like, ‘What the fuck?’

I suggest that despite how different this new album is to Departures, his second solo record which came after 2005’s Tea & Sympathy, to him it would no doubt seem a natural evolution. “Yeah,” he concurs. “Totally. But at the same time, I can understand why some people when they heard ‘Battleships’ for example, were like, ‘What the fuck?’

“Because for me, that was part of the whole evolution of making that record, going through all the processes of getting to that song, but that ended up being the first thing that a lot of people heard.”

Civil Dusk is very much a return to vintage Fanning, for wont of a better phrase. Where 2013’s Departures was much more of a rock record, this new one is closer to his solo debut in that the songs, all of which were built around acoustic guitar and piano as he’s explained, are softer and more intimate, there’s more of a folky vibe, a rootsy vibe.

This isn’t to say there aren’t capacious and loud moments. ‘Wasting Time’ is almost a throw-back to the Powderfinger days, and ‘Change Of Pace’ too is upbeat and up-tempo, chugging along, very aptly named, appearing as it does mid-album after a couple of slower numbers. Sonically, the album is very warm as well, it throbs with a low warmth, due in large part to Fanning’s want to use only timber stringed instruments.

“It’s what appeals to me, it’s what actually hits me in the chest when I’m listening to music,” he says on this warmth. “I’m totally open to synthesisers and whatever else, but even when it comes to guitars, I prefer an acoustic guitar to an electric guitar, just the sound when I’m writing, I feel that richness. When you’re sitting playing with it, you feel it in your body.

“You do with an electric guitar as well, but it’s manufactured a bit, and that’s why my favourite thing to write on is a piano, because it’s like a fucking band. It’s massive and delicate and super melodic and has all those different ways you can voice things… so that’s why I wanted to do that. That’s what gets me. And I listened a lot, while I was writing, I listened a lot to Late For The Sky by Jackson Browne… it’s a fucking masterpiece. I really liked how this record was talking about the problems of society, through the prism of the problems in relationships.

“I’ve always tried to do that, and I’ve never particularly been able to articulate it for a whole record, and this is the closest I’ve got to being able to do that, I reckon.”

It’s fair to say that of any of Fanning’s records, whether on his own or with Powderfinger, Civil Dusk is his Late For The Sky. And this isn’t comparing Fanning to Browne. It’s comparing a style of songwriting, and in this instance, Fanning has produced some of his best work.

***

We finish up the formal part of the interview but stay sitting where we are, looking out again at the view from our vista in this ranging garden up on a hill on the New South Wales north coast. Fanning asks me what music I’m listening to at the moment, and we spend the next ten minutes or so discussing what we’re hearing that we like, what’s worth getting into. He writes a few of my suggestions down in his phone, always on the lookout for something new to stimulate his never-ending lust for good music.

He’s added something of his own to that canon with Civil Dusk. Whether it strikes as many chords as his solo debut, remains to be seen. Tea & Sympathy was an extremely high bar to set after all – indeed, as I drove up here, I couldn’t get ‘Wish You Well’ out of my head, having listened to it as part of the research for this story.

Regardless, with this new album, he’s done something worthy, something good.

“Well, I guess I’m in a situation where I’m starting to feel more comfortable with the idea of having been in a band that was really, um, popular,” he muses when I ask him where he’s at, as an artist. “I’m starting to have a better understanding now of why as well. Because we never thought about that stuff when we were in the middle of it, we were always thinking about what we were doing next.

“I guess now I’ve had a bit of time to look at it. And it’s from what people tell you, how the songs of the band impacted their life, concerts or whatever, and I’m really proud of what we did. I think it’s really good, and so far has stood the test of time. It’s 20 years in September since Double Allergic came out actually.”

We both marvel at that thought – how can it be two decades since the release of one of the band’s most enduring albums? Fair boggles the mind. Fanning’s come to terms with it though, as well as the rest of the band’s success and it seems to have set him up well, for where he’s at today.

“I’m really excited about getting connected again with writing music that hits me really hard, and that will make an impact on people, emotionally. Primarily on me,” he concurs. “And I’m the only barometer that I really have.

“And obviously Nick, we’ve got a studio together now, so it’s pretty likely that we’re gonna be making a lot of records together for a long time. I’m really excited about the idea of just keeping on making records. I didn’t know, when I turned 40, whether I wanted to keep doing it or just try and do something else with my life… it took me a little while to work out what I wanted to do.”

“Making a break from living in Brisbane and being in Powderfinger has really invigorated me as well, given me a lot of energy to get back into work,” he adds. “And now having a studio, with this horrible view…” Another laugh.

I tell him it’s paying dividends, that I’ve been enjoying the record, and that it’s a grower, an album you really need to explore. “I hope that’s [the case], I would hope that it takes ten listens to go, ‘Oh fuck, that’s fuckin’ awesome’, the back of the record especially,” he enthuses.

“Because you know, from growing up listening to records, you tend to start with track one and you go through and get to know the back of the record later, maybe months down the track. And we put a lot of work into the sequencing with that in mind, so that there’s rewards for perseverance.” Another laugh. “That’s the thing with working with Nick, we both put such value on the ‘album’, because that’s how we grew up loving music. I would hope that that would have some impact on younger people who listen to this record. And with people more my age too I guess.”

Soon afterwards, we finish up properly and Fanning walks me out the front to where I’ve parked the truck. We shake hands and he stands for a bit before turning around and walking back towards the studio where DiDia is still tinkering. He’s in a good place, and regardless of whether he wakes with that feeling of unease or not, it’s translated into some deep and thoughtful music, which befits the man responsible for some of this country’s most iconic songs.

It may be the civil dusk before a brutal dawn, but Bernard Fanning is doing all he can to make sense of that. And that’s all he can do.

Civil Dusk is available from August 5 through Universal Music. The second instalment, Brutal Dawn, will follow in early 2017.

Now home to the likes of the lo-fi rock of Sunflower Bean; the roots/rock hybrid that is Seratones; the unhinged punk roots of Fat White Family; the country of The Felice Brothers; Jon Spencer’s disjointed side-project Heavy Trash, Fat Possum has indeed changed its focus. What hasn’t changed though, is the quality of the acts that call the label home – sure, it’s different music, it’s not as hectic and chaotic as it would have been in the early ‘90s, but Fat Possum is still very much alive, still very much focused on what they see as good music.

Now home to the likes of the lo-fi rock of Sunflower Bean; the roots/rock hybrid that is Seratones; the unhinged punk roots of Fat White Family; the country of The Felice Brothers; Jon Spencer’s disjointed side-project Heavy Trash, Fat Possum has indeed changed its focus. What hasn’t changed though, is the quality of the acts that call the label home – sure, it’s different music, it’s not as hectic and chaotic as it would have been in the early ‘90s, but Fat Possum is still very much alive, still very much focused on what they see as good music.

“Civil Dusk, the term actually comes from civil twilight, which is a photography term,” he tells me. “It’s when the sun has gone down beneath the horizon. Scientifically, I think it’s when the sun is six degrees below the horizon. But pretty much everything is still visible, but not in direct light. And it looks different. So that idea, that metaphor…”

“Civil Dusk, the term actually comes from civil twilight, which is a photography term,” he tells me. “It’s when the sun has gone down beneath the horizon. Scientifically, I think it’s when the sun is six degrees below the horizon. But pretty much everything is still visible, but not in direct light. And it looks different. So that idea, that metaphor…” I suggest that despite how different this new album is to Departures, his second solo record which came after 2005’s Tea & Sympathy, to him it would no doubt seem a natural evolution. “Yeah,” he concurs. “Totally. But at the same time, I can understand why some people when they heard ‘Battleships’ for example, were like, ‘What the fuck?’

I suggest that despite how different this new album is to Departures, his second solo record which came after 2005’s Tea & Sympathy, to him it would no doubt seem a natural evolution. “Yeah,” he concurs. “Totally. But at the same time, I can understand why some people when they heard ‘Battleships’ for example, were like, ‘What the fuck?’

As a result, Nowak and a handful of other top pilots have begun to distance themselves from the organised racing aspect, preferring instead the more renegade freestyle side to a pastime with almost limitless possibilities. “It’s kinda the same as skateboarders, they go out there and they make those videos,” he smiles. “You’ve got the rebels that just wanna make the videos and lead the lifestyle, then you’ve got the guys who wanna go to the competitions. I’m the guy that just wants to be the rebel and lead the lifestyle.”

As a result, Nowak and a handful of other top pilots have begun to distance themselves from the organised racing aspect, preferring instead the more renegade freestyle side to a pastime with almost limitless possibilities. “It’s kinda the same as skateboarders, they go out there and they make those videos,” he smiles. “You’ve got the rebels that just wanna make the videos and lead the lifestyle, then you’ve got the guys who wanna go to the competitions. I’m the guy that just wants to be the rebel and lead the lifestyle.”

We based ourselves in East Nashville (thank you AirBnB), an area of town that over the past five or six years has blossomed from a working class neighbourhood into a tight-knit community of young families and single twenty-somethings, renovated little cottages on tree-lined streets and, of course, a thriving venue, restaurant, food truck and music scene.

We based ourselves in East Nashville (thank you AirBnB), an area of town that over the past five or six years has blossomed from a working class neighbourhood into a tight-knit community of young families and single twenty-somethings, renovated little cottages on tree-lined streets and, of course, a thriving venue, restaurant, food truck and music scene.

The former group are fine at what they do, but are hardly my cup of tea. McReynolds though, with his group behind him, huddled around the one mic playing the sweetest bluegrass you’ll find anywhere replete with perfect vocal harmonies, was astounding. As was Charlie Daniels and his band – man, their version of ‘The Devil Went Down To Georgia’ was incendiary, Daniels himself on fiddle, he almost set it alight, went through at least two bows during the course of the song – magical stuff.

The former group are fine at what they do, but are hardly my cup of tea. McReynolds though, with his group behind him, huddled around the one mic playing the sweetest bluegrass you’ll find anywhere replete with perfect vocal harmonies, was astounding. As was Charlie Daniels and his band – man, their version of ‘The Devil Went Down To Georgia’ was incendiary, Daniels himself on fiddle, he almost set it alight, went through at least two bows during the course of the song – magical stuff. Big mistake – this was so hot, we couldn’t finish it. I tried hard, it tasted so good. But I feared permanent damage to my taste buds, and so had to leave some behind. Highly recommended, but note they don’t muck around with their spice levels – I’m still sweating.

Big mistake – this was so hot, we couldn’t finish it. I tried hard, it tasted so good. But I feared permanent damage to my taste buds, and so had to leave some behind. Highly recommended, but note they don’t muck around with their spice levels – I’m still sweating.

Still on food, and food other than BBQ, our first night in town we were hosted at Eighty3, the restaurant attached to the Madison. I feel I must apologise to executive chef Max Hussey, who I’d met in the lobby earlier in the day, because by this stage of our trip, all I wanted was something simple and familiar and so I ordered steak frites. Most unadventurous.

Still on food, and food other than BBQ, our first night in town we were hosted at Eighty3, the restaurant attached to the Madison. I feel I must apologise to executive chef Max Hussey, who I’d met in the lobby earlier in the day, because by this stage of our trip, all I wanted was something simple and familiar and so I ordered steak frites. Most unadventurous. We head from there to Rock ‘n’ Soul, which by comparison seems lacklustre. It’s not, but perhaps don’t go and walk through straight after the Civil Rights. It does cover a lot of ground though, from the blues players heading north in the early part of the 20th century, the bustle of Beale Street at the time where players came to ‘make it’ (including Mr BB King), to the birth of soul and rock ‘n’ roll over at Sun Studios. It’s only a small museum, but it does a good job of keeping things precise, giving you a nice overview from which you can then explore in more depth by heading to Sun or Stax or one of the many other musical museums in town.

We head from there to Rock ‘n’ Soul, which by comparison seems lacklustre. It’s not, but perhaps don’t go and walk through straight after the Civil Rights. It does cover a lot of ground though, from the blues players heading north in the early part of the 20th century, the bustle of Beale Street at the time where players came to ‘make it’ (including Mr BB King), to the birth of soul and rock ‘n’ roll over at Sun Studios. It’s only a small museum, but it does a good job of keeping things precise, giving you a nice overview from which you can then explore in more depth by heading to Sun or Stax or one of the many other musical museums in town.

Wide, flat roads and tired looking houses, run down cars and shops with boarded windows. It’s confronting in many respects, and seems like a different city from a different time, compared to the more gentrified areas scattered about the Big Easy, one of America’s most famous towns.

Wide, flat roads and tired looking houses, run down cars and shops with boarded windows. It’s confronting in many respects, and seems like a different city from a different time, compared to the more gentrified areas scattered about the Big Easy, one of America’s most famous towns. We wander further down Frenchmen onto Decatur Street, which leads into the Quarter proper, and find ourselves in the divey Aunt Tiki’s, a black hole of a bar open 24 hours a day, a clutch of regulars sitting down the front, dank and dark, a truly beautiful place where I feel completely at home, joking with the two bartenders (one of whom has had more to drink than I), sipping on Jack Daniels with Budweiser chasers, just soaking up a New Orleans Friday night.

We wander further down Frenchmen onto Decatur Street, which leads into the Quarter proper, and find ourselves in the divey Aunt Tiki’s, a black hole of a bar open 24 hours a day, a clutch of regulars sitting down the front, dank and dark, a truly beautiful place where I feel completely at home, joking with the two bartenders (one of whom has had more to drink than I), sipping on Jack Daniels with Budweiser chasers, just soaking up a New Orleans Friday night. The second two nights in town, we stay at the Maison Dupuy on the northern edge of the Quarter. Built on the site of America’s first cotton press, it’s now a grand old dame of a hotel, a collection of five buildings grouped around a pool and courtyard, an old time opulence about it that makes it more endearing than high-end. We base ourselves there as we explore the rest of the Quarter, including the historic Voodoo Museum, Café du Monde and the Hotel Monteleonewhich has a revolving carousel bar and serves up audacious cocktails and turns out to be a good spot to watch the more upscale Quarter clientele and watch the LSU game on the televisions about the wood-paneled room.

The second two nights in town, we stay at the Maison Dupuy on the northern edge of the Quarter. Built on the site of America’s first cotton press, it’s now a grand old dame of a hotel, a collection of five buildings grouped around a pool and courtyard, an old time opulence about it that makes it more endearing than high-end. We base ourselves there as we explore the rest of the Quarter, including the historic Voodoo Museum, Café du Monde and the Hotel Monteleonewhich has a revolving carousel bar and serves up audacious cocktails and turns out to be a good spot to watch the more upscale Quarter clientele and watch the LSU game on the televisions about the wood-paneled room.